I am currently working up an article about Snowdon tourism in the nineteenth century for an upcoming special issue in Studies in Travel Writing. Inevitably, this means that some parts of the initial draft got the chop as they meandered too far from the overall theme of the article in which I explore historic tourists’ emotions in relation to their travelled surroundings. But instead of throwing them into the virtual waste paper basket, they get a second lease of life here.

As a disclaimer, I should add that the two examples below have been cut from two different segments in the overall article, so they do not “talk” to each other. Rather, they give an inkling of the great variety of comments found in the Snowdon visitors’ books.

____

Women’s voices

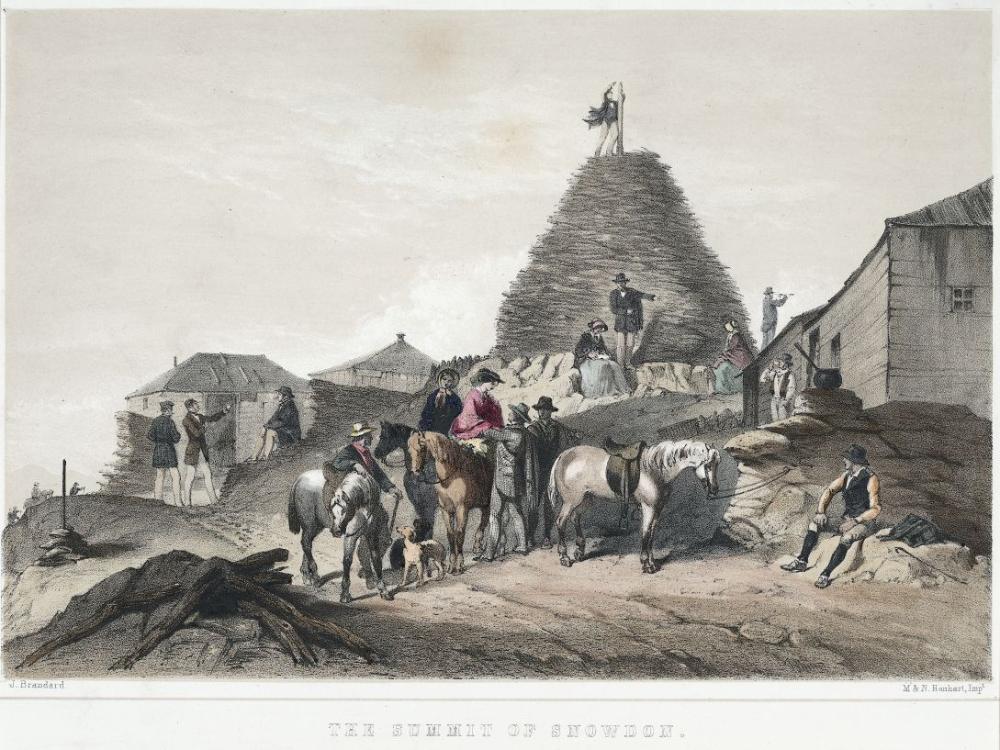

Although only few of the Snowdon visitors’ books have survived, in their sum they still give a representative impression of the development of tourism over the course nineteenth century. With the emergence of tourist agencies in the middle of the nineteenth century which, as a side effect, encouraged a growing number of women to travel independently, women’s names appear in increasing number among the signatories of the visitors’ books. In fact, modern tourism in the form of providing packed tours to large groups of paying customers is inherently tied to the exploration of Wales:

It is arguable that Cook’s real beginning as a “mass excursionist” was the Liverpool-Caernarvon [sic] trip of 1845. The tourists travelled by rail to Liverpool, from where they took a steamer to Caernarvon—with an ascent of Snowdon as a grand climax.

Sharma, 2004 55

This new type of tourist industry enabled women for the first time not only to travel more independently on the domestic tourism circuit, evident in the Snowdon visitors’ books, but also further afield to foreign countries by providing closely monitored packages that ensured the safety and respectability of the unchaperoned and often single female traveller (Urry & Larsen, 2011 40).

Source: Women’s Archive Wales, People’s Collection Wales.

Although entries in the Snowdon books written entirely by women are few and far between, their inscriptions deserve recognition as travel writing. This is particularly apparent when compared against the more prestigious and prototypical forms of the genre, such as the published account in essay or book format in which male authors dominate the market to this day.

Source: STORIEL, Gathering the Jewels, People’s Collection Wales.

Entries like the one by the Misses Newell and Halliday not only offer insights into women’s leisured movement through the landscape, but also give evidence of their relation as female customers to male service providers, such as guides and inn proprietors:

Septr.24 [1845] Miss Newell & Miss Halliday ascended Snowdon with Thomas Jones from Beddgelert & were surprised & delighted at the entertainment afforded them at the top by John Roberts who deserves to prosper for his activity & ingenuity – & we sincerely hope with the blessing of God he will[.]

Snowdon Visitor’s Book, 1845–47 n.p.

Unfortunately, the above message contains no reference to the weather and it must therefore be presumed that if Newell’s and Halliday’s hopes of attaining a view had failed, a resulting disappointment would have been dispersed by the excellent service rendered by Thomas Jones and John Roberts. Considering the time of composition of the above message, these short texts may also help offer correctives to possibly histrionic, false assumptions regarding gender relations and respectability in a sphere of leisurely travel. Here are two women trekking through open country and paying several men for their services without any sense of potential impropriety.

Source: National Library of Wales, Wikimedia Commons.

Observations on the use of Welsh

A message by one Hywel Griffith displays the separation between public statement (the quality of the hostelry service) and personal admiration of the travelled terrain as it neatly divides the message into English prose and Welsh verse:

Sept 8th/62 Howel Griffith from Beddgelert passed the night here and found the accommodation very good & reasonable

“Ar y Wyddfa ar weddfawr”

Wele fi yn yr hwyl fawr.

“Ar aruthr grib Eryri”

Mewn llawen mwyaf wele ni.

Y Wyddfa uchelfawr rhyfed[d]ol dy fri

Mae dringo dy Goryn [sic] yn galed i mi.

Ond eto maeth fryniau ath gymoed[d] i gyd

Yn codi fy ngolwg at Brynwr y byd.(translation: On Snowdon in great form / Behold me in great spirit. / On Snowdonia’s great ridge / Behold us in our greatest spirit. / Highest Snowdon, your renown is extraordinary / Climbing your crown is difficult for me. / Yet the richness of the mountains and valleys all / Lifts my eyes to the Redeemer of the world.)

Snowdon Visitors’ Books, 1863-66 12

Interestingly, there is a level of ambiguity in the English part of the entry. This may be owed to language interference as English may not have been Griffith’s preferred language. As it is, it remains unclear whether he was indeed from Beddgelert or whether he had used one of the popular routes with the village as the base for his ascent.

References

Sharma, K. K. 2004. Tourism and Culture. 2nd ed. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons.

Snowdon Visitor’s Book, 1845–47. 1845–1847. NLW Minor Deposit 34A. Aberystwyth: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales.

Snowdon Visitors’ Books, 1863–1889. 1863–1866, 1883–1885, 1886–1889. NLW MS 16083C, NLW MS 16084C, NLW MS 16085C. Aberystwyth: Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru/National Library of Wales.

Urry, John, and Jonas Larsen. 2011. The Tourist Gaze 3.0. 3. London: SAGE.