The below is the original, unedited article I wrote for publication in the Dictionary of Welsh Biography, or in short the Bywgraffiadur, as part of my work as the Community Outreach Officer of the Diversity Project. The aim of this project is to collect names and produce articles about people who have a strong association with Wales, but who in previous decades have been overlooked. In due course I will provide links to the published English and Welsh versions.

If you would like to find out more about the Diversity Project of the Bywgraffiadur, please follow this link: https://biography.wales/amrywedd.

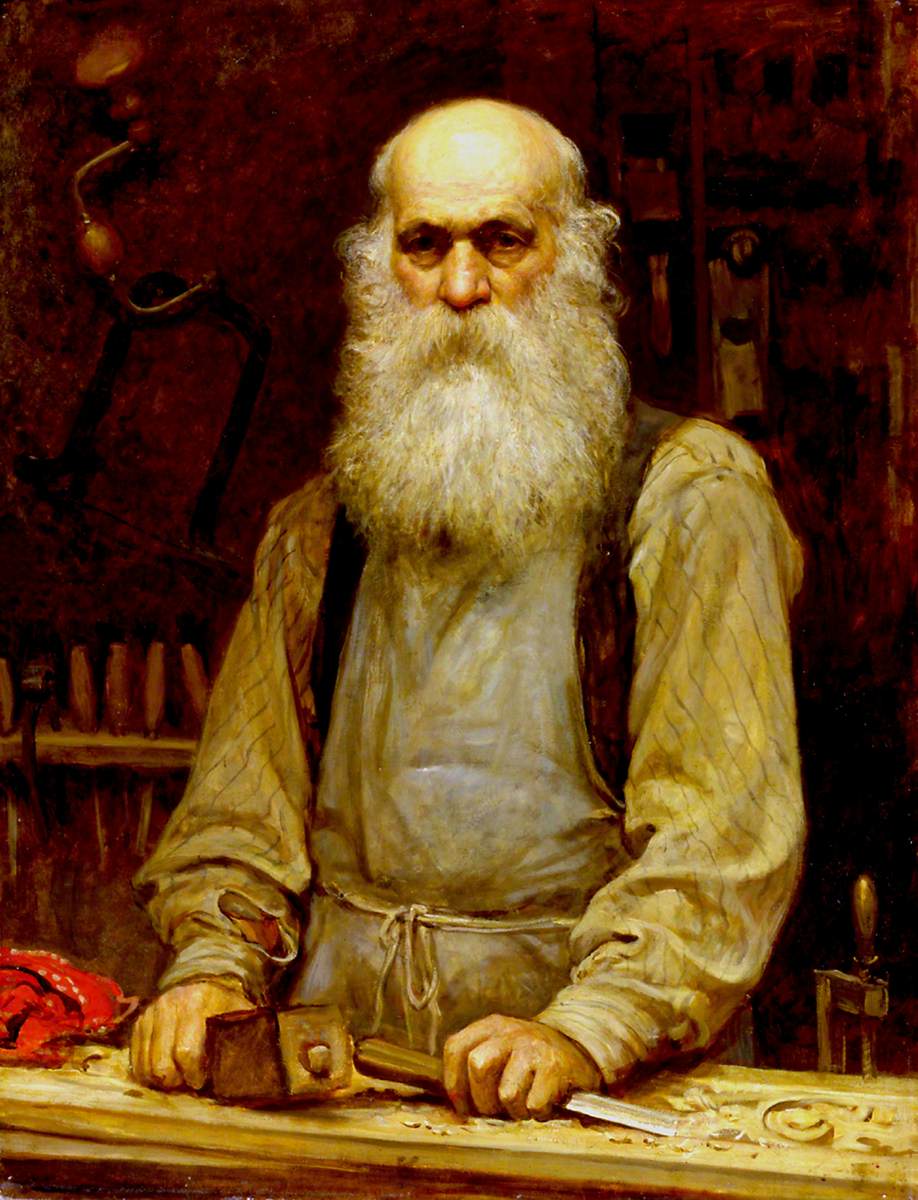

Hubert von Herkomer was born on 26 May 1849 in Waal near Landsberg in the German kingdom of Bavaria. He was the only child of Lorenz Herkomer (1815–1888), a master-joiner, wood carver and occasional draftsman, and Josephine (neé Niggl, 1822–1879), the daughter of a schoolmaster, who shared a happy and tender marriage. Lorenz is said to have declared on the birth of his son, Hubert ‘shall be my best friend, and he shall be a painter’.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Feeling restricted by the political and religious constraints after the failed 1848 revolutions in several of the German states, his parents decided to emigrate to America when Hubert was two years old. Accompanied by Lorenz’s brother, Hans, also known as ‘John’ (1821–1913), the Herkomers lived in New York City for one year before moving on to Rochester and Cleveland, Ohio. Lorenz made a living from his carpentry, but the lack of opportunity for more artistic work prejudiced him against life in the USA. Thanks to her upbringing as a schoolmaster’s daughter, Josephine was a skilled musician, playing the violin and piano. She contributed to the family income as a music teacher, even though she did not yet speak English. Hubert appeared to have inherited his parents’ creative sensitivities as he made his own wooden toys and enjoyed singing and playing the piano throughout his childhood. However, as the climate negatively impacted Hubert and Josephine and Lorenz struggled to find creative commissions, the family left America in May 1875 to settle in Southampton, England.

Source: Southampton City Art Gallery

Source: Hubert von Herkomer, R.A.; a study and a biography

Living in a modestly furnished house in Windsor Terrace, Josephine continued with her work as a music teacher, thus earning most of the family’s income. Lorenz set up a furniture workshop at home and worked poorly-paid odd jobs. He also took on Hubert’s education, teaching him the principles of woodwork and drawing. It was only at this time that Hubert had his first English lessons through one of his mother’s pupils. As the family income was extremely constrained, Lorenz became a teetotal vegetarian and gave up smoking as a means to stretch the budget. His friends and acquaintances thought this was most eccentric, but Hubert, out of admiration for his father, adopted the diet for himself. At fourteen years of age, he eventually entered art school, but struggled with the art styles promoted by his tutors and their teaching methods which relied on creating copies of master works.

In the first half of the 1860s, the Herkomers moved into a shared house with Josephine’s sister and her husband, who had both recently emigrated from Germany and worked as professional musicians. By 1861, Hubert’s parents had become naturalised British citizens. In 1865, Lorenz took his son to Munich to study art while he, Lorenz, worked on a commission for a set of carved figures. Their trip was cut short by the expiry of Lorenz’s British passport after only six months which forced an early return to Southampton. Hubert continued his formal studies in 1866 by enrolling for one term in the South Kensington schools, boarding at a house in Wandsworth Road, after which he returned to Southampton. He also began giving drawing and music lessons and, together with a friend from art school, he organised his first public art exhibition. Hubert sold his first picture for £2 2s. Returning to Kensington in 1867 for another term, he first encountered the works of Frederick Walker (1840–1875) which left a permanent influence on his own art work. A handful of commissioned illustrations in English papers soon followed. In summer 1868, Herkomer went on his first sketching tour, selling one of his drawings to his friend, the author Eustace Hinton Jones (1839-1881), and an illustration published in the monthly evangelical periodical Good Words. This early on in his career as social realist artist, Herkomer still supplemented his modest income with music lessons, while living in shared lodgings with a friend from art school. Herkomer’s commercial break came with the submission of an unsolicited illustration to the weekly illustrated newspaper, Graphic, with the manager, William Luson Thomas (1830–1900), welcoming any further work. During the summer of 1870, Herkomer exhibited at the Dudley Gallery and established himself as a new artist on the British scene.

In spring 1871, Herkomer returned with his parents to the Bavarian uplands for an extended sketching tour. He used the opportunity for producing landscape works in watercolour and oil and also prepared more illustrations for the Graphic, thus securing himself and his parents a steady stream of income during their time abroad. Herkomer’s income that year allowed him to return with his parents in the next for an extended holiday in Bavaria, while working on a large oil painting that eventually became ‘After the Toil of the Day’. He later submitted this canvas to the Royal Academy for exhibition in 1873. Until 1904, over 150 of his works would be shown there.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

On 10 January 1872, Hubert Herkomer became a naturalised British citizen. The ceremonial oath of allegiance was witnessed by Sills John Gibbons (1809-1876), the Lord Mayor of London, and the Certificate of Naturalisation granted by Henry Austin Bruce (1815–1895), the Home Secretary.

Through a series of chance meetings with potential purchasers, Herkomer eventually sold a watercolour drawing, ‘Fairy Allegory’, to Charles William Mansel Lewis (1845–1931) from Llanelli, in 1873. This purchase laid the foundation of a life-long friendship between the two men. Not only was Mansel Lewis a patron and art collector, but also an artist in his own right who shared many of Herkomer’s aesthetic sensibilities. His friendship with Mansel Lewis would attract Herkomer to Wales in the next years in more than one way.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Lady Lever Art Gallery

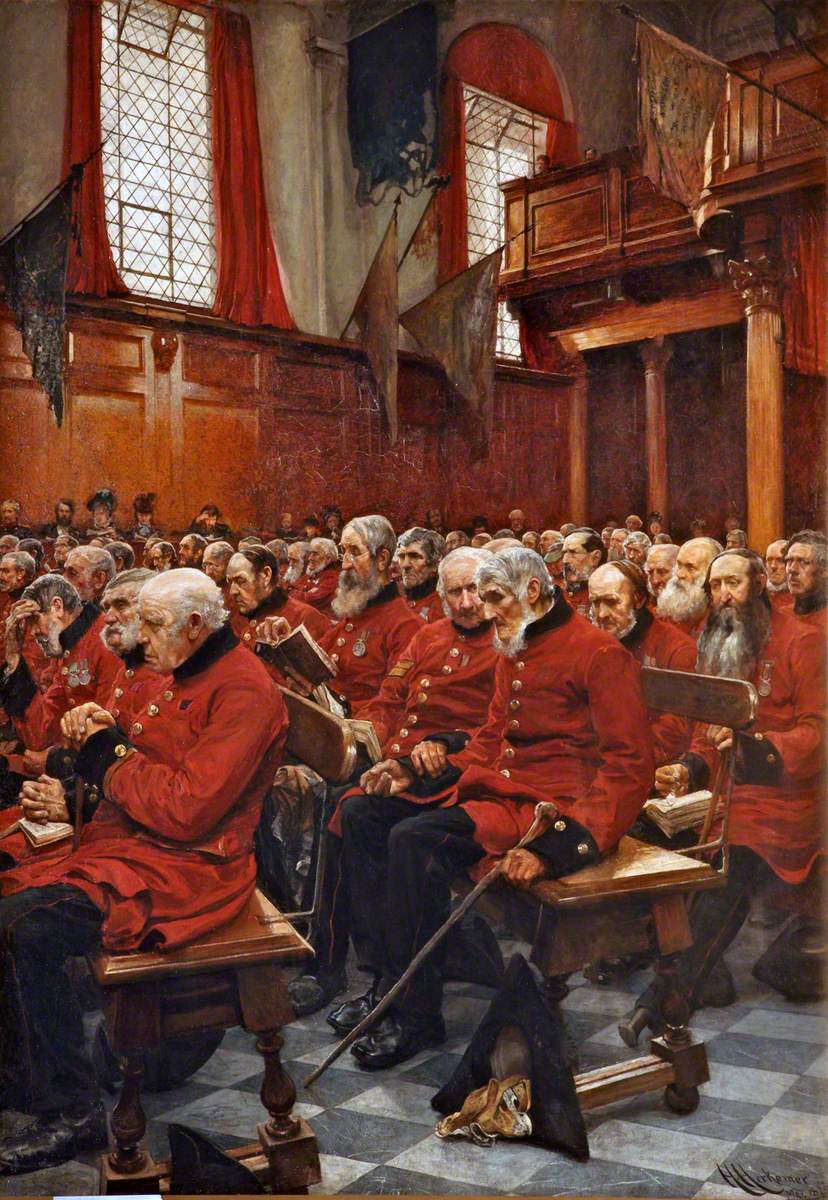

With the earnings from the sale of ‘Fairy Allegory’ and the commission of another, Herkomer rented his parents a cottage in Bushey, Hertfordshire, to where they retired in 1873, while he remained living in Chelsea. At around the same time, Herkomer married Anna Caroline Ada Weise (1840–1883), a fellow German immigrant from Berlin. They had two children, Siegfried Hubert (1874–1939) and Elsa Anna Iole (1876–1938), however, their marriage proved not a happy one. According to Herkomer’s own statement, he married Anna in an attempt to make her happy. She suffered several chronic illnesses. To assist with Anna’s care, Herkomer hired a nurse, Eliza Louisa ‘Lulu’ Griffiths (1849-1885) from Ruthin. To cut down on the costs in the creation of his first major work, ‘The Last Muster’ (1875), Herkomer worked mostly from home. This decision forced him to rely entirely on an old wood engraving, other previous sketches, notes and his visual memory. The large painting was exhibited to great acclaim at the Royal Academy and also established his international fame, winning him a gold medal at the 1878 Paris Exposition. Despite the accolades heaped on Herkomer, he was not quite satisfied with the final result as it did not match his original vision. Most of the proceedings from the sale of the picture covered the high medical costs for Anna’s health care.

Source: Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Source: Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Source: Penlee House Gallery & Museum

To prevent becoming known as a painter of pensioners in uniform, Herkomer deliberately went against the grain and produced several large works with German subjects over the next years, including a portrait of Richard Wagner (1813–1883) for the German Athenaeum, an exclusive society of German emigrees in London.

Following the successful exhibition at the Royal Academy, Anna’s health went into decline, which precipitated Lulu Griffiths and her younger sister Margaret ‘Maggie’ Griffiths (1854–1934) moving in with the Herkomers to look after her and the children. In 1878, Herkomer bought his parents a house in Landsberg am Lech and they returned to Bavaria, near their old home in Waal, while he relocated his family to Bushey. During this time of familial strain and financial worry, Herkomer’s physical and mental health suffered and he, too, now relied on Lulu’s nursing. On his mother’s death only a year later, his father returned to the UK and moved in with his son, who by then had been elected an Associate of the Royal Academy. As a monument to his mother’s memory, Herkomer designed and commissioned the construction of a pseudo-medieval tower, the ‘Mutterturm’, attached to the Landsberg house. It still stands to this day.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

During the summer of 1879, Herkomer and Mansel Lewis went on their first of several drawing and camping trip in Snowdonia. These excursions lasted until 1884. During their first outing they camped for several weeks near Capel Curig. In later years, Herkomer brought along a portable hut for himself and Mansel Lewis to serve as their studio in all weathers. These excursions initiated Herkomer to Welsh landscape painting and over the years, he produced several large works in oil and watercolour, many of which he exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Coinciding with his annual journeys into Wales, Herkomer began shifting his subject focus from genre and landscape painting towards portraiture. Over this career, he went on to paint over two hundred portraits, most of them showing leading figures in British society such as Prime Minister Robert Cecil (1830–1903), Thomas Hardy (1840–1928), John Ruskin (1819–1900), Herbert Kitchener (1850–1916), Archbishop of Canterbury Frederick Temple (1821–1902), business owners Owen Owen (1848–1910) and Thomas J. Lipton (1850–1931), Lord Kelvin (1824–1907), and a deathbed portrait of Queen Victoria (1819-1901), to name just a few. But perhaps Herkomer’s internationally most famous portrait was that of a neighbour, Katherine Grant (1865–1952), which became colloquially known as ‘The Lady in White’ (1885). The painting travelled several times between Europe and North America to great public acclaim and won him many awards.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1881, the Herkomer family split up for health and work reasons. On doctor’s advice, Anna and the children, Siegfried and Elsa, travelled to Germany and Austria in the company of Maggie Griffiths. At the same time, Herkomer, his father and Lulu Griffiths went to the USA for work. According to Herkomer, Lulu came along on his father’s request. However, others have suggested that he, Hubert ad Lulu were already in a committed relationship as the marriage with Anna had entirely broken down. Her journey to the European mainland merely confirmed the domestic situation. On his return from abroad in 1883, he received news that Anna had succumbed consumption in Vienna. The news of her terminal illness had deliberately been withheld to prevent him breaking off the trans-Atlantic journey. Lulu and her sister, Maggie, took over the organisation of the household. Before long, Herkomer’s uncle, Hans, and his family relocated from Ohio and settled nearby.

During Herkomer’s time in America, a large building had been constructed in Bushey to serve as a future art school where he would teach without taking a fee. The school opened in October 1883 to an initial class of twenty-five students and remained in operation until 1904. When it was time to retire, Herkomer had taught over 500 students, male and female. Among his most successful students was Lucy Kemp-Welch (1869–1958), who specialised in painting horses and famously illustrated the 1915 edition of Black Beauty. In 1905, she took over the art school and directed it until 1926. Many of his students settled in Bushey thanks to his help in building small studios near the school. The village quickly turned into an artists’ colony of about 100 creatives before the end of the decade. The combined successes of his prize-winning large paintings, his election as ARA and lecturing at his own art school in Bushey culminated in his appointment to the Slade Professorship of Fine Art at Oxford, replacing none other than John Ruskin. Herkomer held the position until 1894.

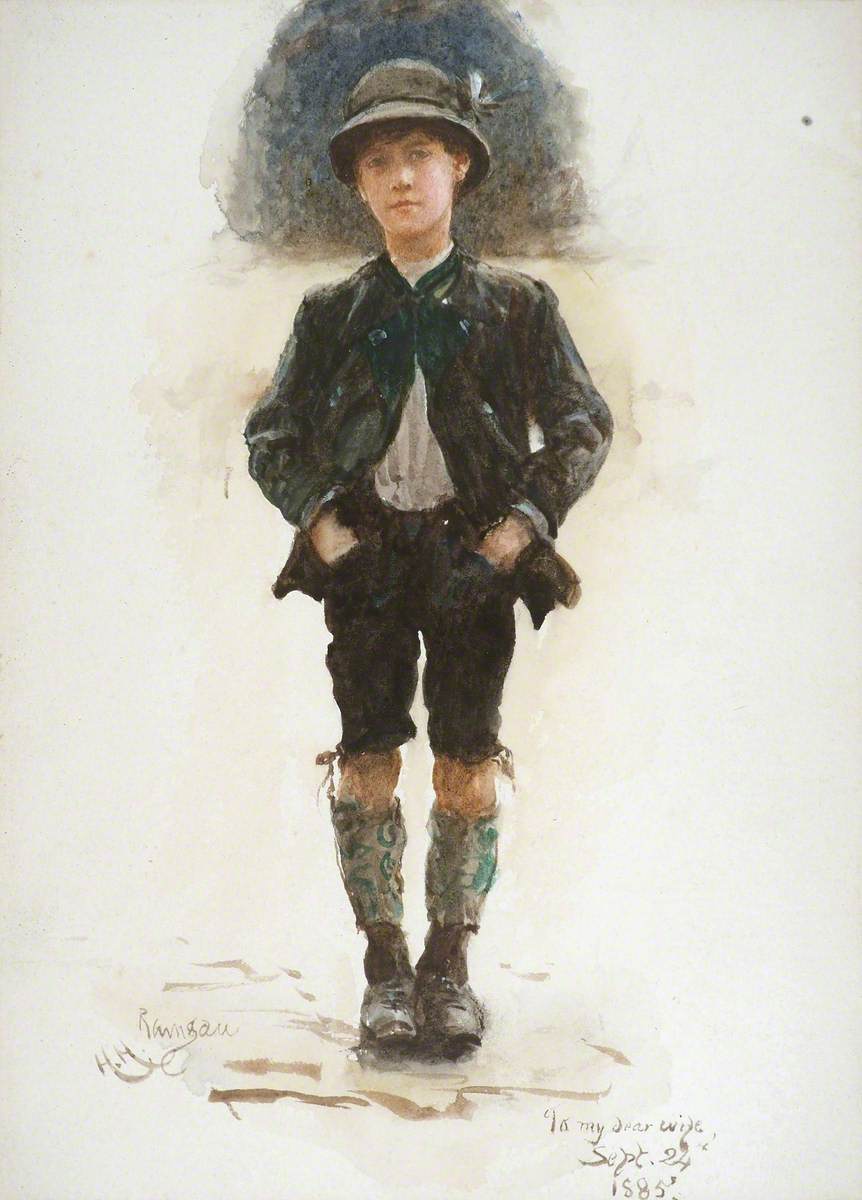

Source: The Herkomers, vol. 1

These rapidly following successes coincided with further happiness and tragedy in Herkomer’s private life. On 12 August 1884, Herkomer married Lulu Griffiths in her hometown, Ruthin. Their marriage was a happy one, but tragically cut short. Lulu suffered a miscarriage as the result of coming to the rescue of a small child from being run over by a horse and carriage. Three months later, on 24 November 1885, she died suddenly of a heart attack. Over the summer, Herkomer had already made plans for a work journey to the USA. Accompanied by his father, he set out to New York where, after disembarkation, he suffered a complete breakdown grieving Lulu’s death. During this journey, he also met with the Boston architect, Henry Hobson Richardson (1838–1886), who worked up the plans for Herkomer’s grand family house and studio, Lululaund, named in memory of his second wife. Built as a mixture of Arts and Crafts, Romanesque and German Gothic styles, the house was constructed between 1886 and 1894. The house featured a complete interior design by Herkomer, electricity generated on site and hot and cold running water in all bathrooms. At a later point, he also built a theatre on the site to write, compose and stage musical dramas.

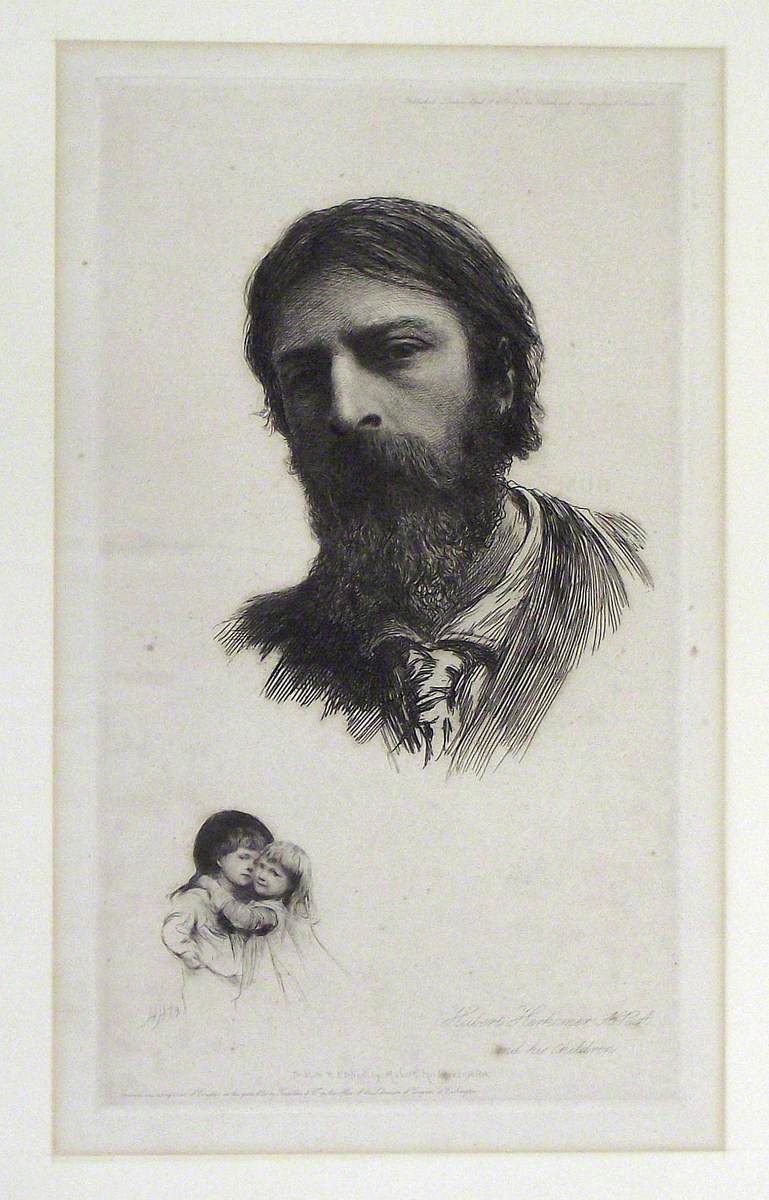

Source: Hubert von Herkomer, R.A.; a study and a biography

Source: Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

After Lulu’s death, Herkomer threw himself into excessive work for several years. So as not to neglect his children, he asked Maggie Griffiths to take them to her family in Ruthin and look after them. In 1888, shortly before the death of his beloved father, Lorenz, he asked her to marry him, but a marriage between siblings in law was against British law. Consequently, Herkomer and Maggie both travelled to Germany in 1889, where he regained his German citizenship. They were married according to German law in Landsberg on 2 September and had two children, Lorenz Hans Lawrence (1889-1922), already born the same month, and Gwenddydd (1893–1927).

Source: Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Following a stream of exhibited work at the RA and several international accolades, Herkomer was elected Royal Academician in 1890. The following years saw his continued restless, high-rate production of largescale landscapes and portraits, the invention of his own reproduction method, ‘Herkomergravure’, and further theatre productions. As ever, the entire family would repeatedly travel to Germany for artistic and leisurely pursuits and Herkomer ventured twice into Italy. In 1899, Herkomer saw the highest German honours bestowed on him as he was ennobled ‘Ritter von Herkomer’, received the ‘Verdienstorden der Bayerischen Krone’ (Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown) and the Prussian ‘Pour le Mérite’ of the civil class for extraordinary personal achievement. This was also the decade in which Herkomer left his visually most striking mark on the Eisteddfod and the Gorsedd of the Bards.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1895, he attended the National Eisteddfod in Llanelli as adjudicator in the art competition under the patronage of Mansel Lewis. On that occasion, he was also invested into the Gorsedd and received the name ‘Gomer’. While he was not impressed by the quality of Welsh art and made some cutting remarks about its sorry state in his adjudication speech, he found the theatricality of the Gorsedd to his liking, producing a sketch of Rowland Williams (Hwfa Môn; 1823–1905) in his gown, golden chain and bishop-like mitre, and Evan Jones (‘Gurnos ‘; 1840–1903). Herkomer was so taken by the event, he enthusiastically offered his services and suggested a re-redesign of the Archdruid’s regalia. The following year, he presided over the opening day proceedings and delivered the presidential address at the Llandudno Eisteddfod. Herkomer completed the new golden torc and crown of the Archdruid in time for the 1897 Newport Eisteddfod and once more took on the adjudication of the art competition. In subsequent years, he produced further drawings and paintings of Hwfa Môn in his new regalia. Herkomer’s perhaps visually most striking contribution was his design for the new 6-foot Grand Sword with its ornate gold handle and large crystal first used in the 1899 Cardiff Eisteddfod. All three of these objects are still in use today.

Source: Geoff Charles, Wikimedia Commons

Despite a pronounced decline in his health due to stomach ulcers, Herkomer continued with his characteristic enthusiasm for portraiture and print, teaching and travelling throughout the first decade of the twentieth century. More accolades in the form of honorary titles, degrees and memberships kept pouring in. In addition to his artistic output, Herkomer also took the time to pen several autobiographical works, most notably My School and My Gospel (1908) and The Herkomers (1910). In 1912, his work was interrupted for some time following a gastric operation for his ulcers. In keeping with his curiosity for any new subject, Herkomer framed a pair of surgeon’s rubber gloves and hung them in his artist studio at Lululaund. That same year, Herkomer and his son, Siegfried, who had worked for Pathé, began making films together. A year later, they converted the family theatre into a film studio and formed the short-lived Herkomer Film Company. Within just under two years, father and son produced seven films, but none of the prints survive.

Hubert von Herkomer died suddenly at Budleigh Salteron on 31 March 1914, to where he had been sent for his poor health. His funeral at Lululaund took place in the presence of family, friends and many British and German dignitaries. He was buried in the family tomb in St James’s churchyard, Bushey, where his father, Lorenz, and second wife, Lulu, had already been laid to rest.

Source: Bushey Museum and Art Gallery

His contemporaries thought Herkomer egotistical and a great talker with an overwhelming personality which was, no doubt, compounded by his physical height, piercing eyes and bushy, black beard which he wore until middle age. Restless and obsessively enthusiastic in every aspect of his artistic pursuits, he liked to impose his aesthetic opinions on others. However, he was also noted for his kindness, affection, humour and cordiality at all times. His habit of close study bewildered several of his portrait sitters. He often stared at them from up close and subjected them to an unending stream of one-sided conversation for fear they might fall asleep. Katherine Grant remembered how crushed with grief he was by Lulu’s death, and recalled that while he estranged people, Herkomer’s intense personality was most likely explained with his longing for sympathy and love. Recognising the effect of his behaviour on his contemporaries, Herkomer himself admitted that his habits ‘are those of a foreigner—my enthusiasm, my outspokenness, my self-possession, my life is un-English. But my art and my feeling for art will always remain English.’

+++

PostScript

Herkomer was a man of many parts. Not content with inventing his own methods of engraving, musical theatre productions and pioneering film, it turns out he was the originator of one of Germany’s first touring car rallies when he established the Herkomer-Konkurrenz in 1907 after he became supremely interested in automobile engineering.

+++

Sources

Lee M. Edwards, Herkomer : A Victorian artist (Brookfield 1999)

Hubert Herkomer, ‘Hubert Herkomer’ in Louis Engel (ed.), From Handel to Hallé: Biographical Sketches (London 1890), pp.135-225, https://archive.org/details/fromhandeltohall00enge

Hubert von Herkomer, My School and My Gospel (London 1908), https://archive.org/details/myschoolmygospel00herk/

Hubert von Herkomer, The Herkomers, 2 vols (London 1910), https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/005717156

Alfred Lys Baldry, Hubert von Herkomer, R.A.; a study and a biography (London 1901) https://archive.org/details/hubertvonherkome00balduoft/

UK, Naturalisation Certificates and Declarations, 1870-1916 for Hubert Herkomer, Piece 002: Certificate Numbers A497 – A746

Andrew Green, ‘Charles William Mansel Lewis, painter’, gwallter, 30 October 2016, https://gwallter.com/art/charles-william-mansel-lewis-painter.html

‘Herkomer’s Art School’, Bushey Museum, https://busheymuseum.org/herkomers-art-school-at-bushey/

Philip V. Allingham, ‘Sir Hubert Von Herkomer, R. A. (1849-1914)’, The Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/herkomer/bio.html

Catherine Hilary, ‘Photographs of Sir Hubert von Herkomer and his family from the Rob Dickins Collection, Watts Gallery’, The Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/painting/herkomer/hillary.html

John Saxon Mills, Life and letters of Sir Hubert Herkomer : a study in struggle and success (London 1923)

‘Sir Hubert von Herkomer, R.A., R.W.S. (British, 1849-1914), Miss Katherine Grant (The Lady in White)’, Christie’s, https://onlineonly.christies.com/s/british-european-art/sir-hubert-von-herkomer-r-a-r-w-s-british-1849-1914-11/138539

‘The Llanelly Eisteddfod’, Evening Express, 23 January 1895, p. 2, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3250739/3250741/27/

‘National Eisteddfod’, South Wales Echo, 31 July 1895, p. 4, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4602247/4602251/97/

‘Professor Herkomer Interviewed’, ‘Professor Herkomer on the Eisteddfod’, The South Wales Daily Post, 31July 1895, p. 3, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3353469/3353472/26 , https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3353469/3353472/27

‘The Eisteddfod’, Western Mail, 2 August 1895, p. 5, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/4332800/4332805/43/

‘The Archdruid’, Evening Express, 12 August 1895, p. 4, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3255029/3255033/78/

‘The Eisteddfod’, South Wales Daily News, 1 July 1896, p. 5, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3737592/3737597/68

‘The National Eisteddfod’, South Wales Daily News, 4 August 1897, pp. 5-6, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3739266/3739272

‘Cardiff National Eisteddfod’, Evening Express, 11 July 1899, p. 3, https://newspapers.library.wales/view/3462058/3462061/47