Back in March this year, I had the privilege to give a talk at Blaenannerch Chapel to a group of people participating in the project ‘Allen Raine: The Opera?‘ by Rowan O’Neill, funded by the Arts Council of Wales and the Lottery. Over the course of half a year, people from the Tresaith and Aberporth communities and surrounding area are creating a sort of community opera inspired by the novels and short stories of Allen Raine. While the author’s name used to hold quite a bit of currency in the English-speaking world a little over a hundred years ago, these days it’s largely Welsh writing in English aficionados and locals who not only have a bit of knowledge about the author, leave alone have read one or two of her many books. To help her project participants along in their Raine journey, Rowan invited me to come to Blaenannerch and give a talk about the author, her link with the locality and why music was and is so important to unlocking her stories.

The essay below is based on the middle section of my talk ‘Allen Raine: The Radical?’ (click here to listen to a recording from the evening) and will also cover some additional material that I didn’t mention on the occasion. In the first of eventually three parts in this series, I focussed on the life of Ada Puddicombe. This second part gives an overview of her entire published works.

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Becoming Allen Raine: pre-history and golden years

Career-wise, Ada was a literary late-bloomer. She had dappled in literary writing already as a young woman by contributing from 1858 to the short-lived magazine Home Sunshine that was published from Newcastle Emlyn. It would take then several decades, before she returned to literary writing in her late fifties. Between 1894 and her death in 1908, Allen Raine published eleven novels and several short stories, showing a tremendous speed of composition, but also proving that rural Welsh settings were inherently literary and attracted a speedily growing readership.

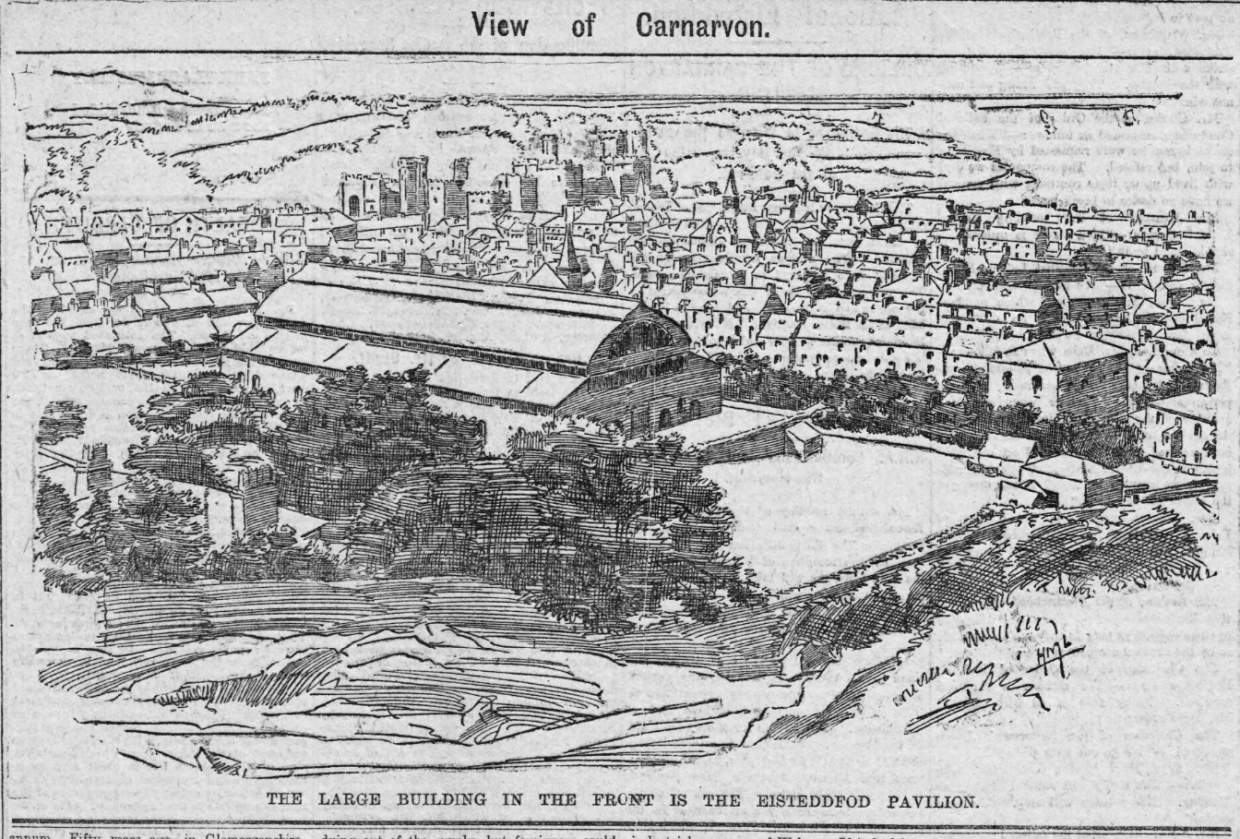

Her first novel was Ynysoer (post-humously republished as Where Billows Roll). This novel was her winning contribution to the 1894 National Eisteddfod in Caernarfon, submitted under the pseudonym Arianwen. Her brother kindly accepted the £25 prize money on her behalf as her illness prevented her from travelling all the way from London.

Source: Welsh Newspapers Online.

Following on her success in the Caernarfon Eisteddfod, Allen Raine turned her hand to poetry. She published her poem, ‘A Sacred Spot’ and translated the dramatic poem ‘Alun Mabon’ by John Ceiriog Hughes, one of Wales’s foremost Victorian poets. Both appeared in O. M. Edwards‘s miscellany Wales: a national magazine for the English speaking parts of Wales over several issues in 1897. Perhaps the translation had more than just a fleeting influence on Raine’s literary development. It might even hold the subliminal key to her her pseudonym, which she stated to have seen in a dream written above her bed. After all, Alun Mabon’s muse in the poem is none other than Menna Rhên.

Despite the early success with publishing poetry, this was not the format for which she became internationally famous. Instead, Raine turned to prose. The period of the late-1890s to early 1900s was clearly a fruitful one in developing her talent as a fast writer. Aside for her predilection of setting her stories in coastal Welsh villages on the model of ‘describe a scene outside your window’, she also came up with her winning formula. Already the first novel published under her now officially adopted pseudonym Allen Raine, follows the pattern of ‘A loves B, who marries C, who loves D, who loves A — remove C and D from the equation (if needs must, kill them)’. Already Raine’s early critics questioned the ‘artistic value’ of using similar settings, characters and following a certain plot pattern. Above all, however, they criticised her for seeking financial success as a commercial author, rather than becoming an author of ideas who lives and dies for art and art only. Clearly not caring much for this ‘valuable’ input, in quick succession, Raine published a new novel almost every year. She launched her brand with A Welsh Singer (1897), continuting with Torn Sails (1898), By Berwen Banks (1899), Garthowen (1900), A Welsh Witch (1902), On the Wings of the Wind (1903), Hearts of Wales (1905) and Queen of the Rushes (1906). In next to no time, she had sold over a million copies and become one of the internationally best-selling authors at the turn of the century.

Above all things, Allen Raine’s novels proved time and again that being a commercial author does not detract from also telling a good story, before dedicating space to developing an idea. In a way, her critics took issue with a supposed lack of reality — and the majority did not come out of the woodworks until after her death. Tellingly, her harshest critics were men who knew Raine was a woman and who were also admirers of Caradoc Evans, the irony being that both, Raine and Evans, essentially wrote about the same communities. The only difference between them was that the former wrote about ‘her’ villagers with affection (but with a healthy dose of critical detachment), whereas the latter wallowed in his disdainful judgement (with a lot of personal emotional involvement).

Source: G. L’Évéque, ‘Allen Raine’, The Lady’s Realm, v.25 (1908/9), p. 38

Being Allen Raine: the silver years

Allen Raine’s rise to fame coincided with her husband’s declining health. If it had not been for her faithful personal aides to whom she dictated her stories and who then spent the remainder of their work day typing up clean copies for subsequent revisions, she would clearly not have been able to publish a new book almost annually. Following Beynon’s death in 1906, Raine began revisiting previously abandoned material not so much because she had run out of ideas, but for her own declining health. What I’d like to term Allen Raine’s silver years covers the period from 1906 and concerns the publication of three volumes, all of which bar one were published posthumously and clearly indicate how her publishers, Hutchinson’s, wanted to reap the final fruits of one of their major cash cows in their catalogue. In order of appearance they are Where Billows Roll (1907), Neither Storehouse nor Barn (1908), All in a Month (1908) and Under the Thatch (1910).

Where Billows Roll was the first collected publication of Allen Raine’s prize-wining Eisteddfod novel Ynysoer that until now only existed in serialized form. Raine had managed to buy back the copyright for her work from the Eisteddfod, but in order for Hutchinson’s to disguise it as something new, the title was changed to something also less obviously Welsh. Unfortunately, this was the only revision. Following from the sophistication of Queen of the Rushes (a deep dive into this novel will follow in the third part of this series), Billows is a let-down, particularly as this is the last novel published during the author’s life time. On the one hand, it contains all the hallmarks of a typical Raine novel: a coastal setting, characters that are associated with particular geographical features in the landscape, lovers who cannot meet. On the other hand, the novel is plagued by flat characterisation and a set of extremely unconvincingly written twins named Iolo and Iola. Really! The most interesting part in this novel is contained in the opening chapter where on less than a page Raine sketches the economic sprawl of the British Empire and its reaches into the Welsh countryside. But only a sketch it is.

Neither Storehouse nor Barn was rushed through publication shortly after Raine’s death as her last completed novel. It chiefly tells the story of a young woman and man, Olwen and Gwil, tramping their way across Wales on their respective ways to Manchester and Liverpool. Following the death of her father, Olwen is looking to move in with her aunt and uncle, while Gwil intents to emigrate to America and become rich by patenting a harvesting machine. After much pearl-clutching by Olwen’s aunt, Susan, some devious machinations by another village girl, Kitty, and Gwil not emigrating, the story returns to a secluded country estate in Wales. Somehow, Olwen and Gwil become the hermit-like servants of a childless squire. I’m not sure if the comparison fits, but this novel could perhaps be summed up as Allen Raine’s version of On the Road — but without the sex! –, as a lot of the conflict arises and resolves through perambulations through the Welsh countryside and the ultimate let-down of English city life. Much like Kerouac’s typing, the story feels episodic, with one thing happening after another, but only hanging together quite losely. It definitely has its charm and, as ever, Raine’s caricature of self-loathing Welsh city dwellers is nothing short of cutting and funny. Sadly, the novel lacks the easy flow of her previous works. This was most certainly her swan song.

While Storehouse had fleshed out only one of Raine’s abandoned story ideas, the All in a Month anthology bundles up nearly all her previously published short stories into one handy volume and, thankfully, without changing them. The title of the collection derives from the first and longest story in the collection. It tells the story of a young woman who has recently started working in a private care institution for mentally ill people. Without giving too much away, this is a mystery story in which the conflict arises from the young woman’s inexperience as a nurse and her work with the patients. Allen Raine’s description of the patients are clearly based on her first-hand knowledge of her husband’s illness and at every point, she shows her deep sympathies for each resident in the care home, from the doctor and staff to each patient and their individual needs and troubles. Not all of the collected stories are equally successful in their treatment, but the strongest stories are the Gothic tale ‘Was it the Wind?’, the painful ‘Betti Wyn’s Christmas’ and ‘A Brave Welshwoman’, telling the story of Welsh emigrants who have settled on the American plains and who experience a raid by Native Americans. Raine, ever the quiet, observing rebel, sneaks in some well-planted anti-settler colonial critique here.

The less is said about Under the Thatch, the better. The premise for the novel is interesting as Allen Raine drew on her own experience of living with terminal breast cancer. There are some ideas and ethical conundrums planted in the initial chapters, such as the quandery of euthanasia and assisted suicide in cases of terminal illnesses or the role of alternative medicine versus Trad Med. However, there is a nasty undercurrent of Cambrophobia throughout where you can ultimately tell that someone else was involved in putting the finishing touches on the novel. Or, to say it with Sally Jones, who said it best: ‘It’s interesting, but it’s not Allen Raine.’ The greatest regret is that this could have been an incredibly bold and difficult work, but sadly Allen Raine was unable to finish it.

Apart from mostly all her novels depending on the established formula of interrupted lovers and detailed descriptions of coastal Welsh village life, another undercurrent links all of Allen Raine’s works. As a great lover of music and accomplished piano player and singer, it was almost inevitable that this aspect of her life found a fictional rendering. The musical culture of the Welsh chapel, folk songs and eisteddfod traditions habitually make their appearance, not bolted on as an artificial means, but rather showing music as a deeply embedded cultural practise in the Welsh countryside. Especially the development of the eisteddfod tradition during the nineteenth century accounts for common peasants’ exposure to formal classical music as was practised in concert halls and on the opera stage. Rather than a clash of musical cultures and tastes, Raine shows how easily Händel sits besides old folk tunes, how drinking songs are polished into respectable chapel music, or how a milking song for a cow is elevated to an aria. But more of that with the next and final installment in this series, when I will discuss Allen Raine’s Welsh Revival novel, Queen of the Rushes, and what it all means.