Summary

In 'The Sprectre of Pont Vathu', Thomas Richards uses typical elements of Welsh folklore to create an original Gothic short story that is trying to pass for a real-life account.

The other day, I shared ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathu’ (1823) on this blog. It is one of my favourite short stories by Thomas Richards (1800-1877), a late-Romantic from Dolgellau who later emigrated to Hobart and there became one of the first settler authors of fiction set in Tasmania. The below write-up is based on a paper delivered at a conference on Welsh Gothic writing held in 2022. It is a little rough around the edges and I plan to go back to it in due course and give it some proper thought and some more flesh and bones, so to say, for submission to a journal. In the meantime, enjoy this excursion into an early example of Welsh Gothic writing.

On 1 November 1825, the quarterly journal The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, &c. published the first of two ‘Cambrian Sketches’ by an anonymous author under the title ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathew’. This was not the first time, however, this story was published, as it had previously appeared in the March 1823 issue of The Brighton Gleaner, who in turn had copied it from a previous issue of the short-lived New European Magazine. The serial life of this Gothic tale reflects the similar publication history of many other stories penned by the London-based surgeon Thomas Richards, formerly of Dolgellau. While a prolific writer of antiquarian essays, character studies of contemporary public figures, short stories, novellas and even an early contribution to the emerging Welsh novel in English, Richards is now virtually unknown in the country of his origin, whereas in Australia he counts among the first contributors to the newly emerging Tasmanian short story.

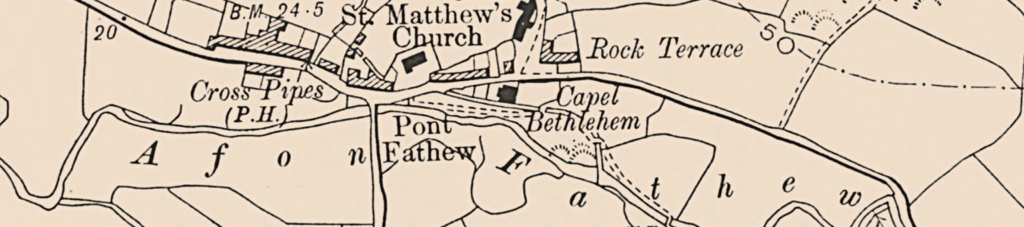

Born in Dolgellau to Elizabeth and Thomas Richards senior in 1800, young Thomas was sent to boarding school at Christ’s Hospital in London at nine years old following the death of his father. In 1815, he entered St Bartholomew’s to train as a medical practitioner, specialising in nervous disorders. In 1832 then, he and his wife gained passage to Tasmania. They settled in Hobart, where Richards died and was buried in 1877. Even though he had only lived in Wales during young childhood, the country never quite lost its hold on Richards, to the point that even in his 1829 Treatise on Nervous Disorders, in which he also discusses visual and audible hallucinations, he could not help himself but include a substantial footnote about the merits of ‘a visit to [his] own native country, North Wales’ with the Golden Lion in Dolgellau serving as headquarter from which to explore the neighbouring valleys (152). And it is here on his family’s stomping grounds between Dolgellau and Tywyn where, like so many of his other stories, Richards locates his Gothic tale of ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathew’.

As Jane Aaron points out, Welsh Gothic novels from the Romantic period ’seem intent on re-enacting the traumas of Welsh history, in the distancing romanticized form of the fateful marriage plot. As yet, however, [these texts] have all been set in the authors’ contemporary Wales’ (Welsh Gothic 36), while at the same time they ‘were initially sold to their readers not as fictions but as “authentic information”’ (Cambria Gothica viii). This also holds true for Richards’ ‘Spectre’ short story. Rather than plunging straight into the action, Richards prefaces the story first with a quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet and immediately plunges into an opening arguments on the nature of ghostly hauntings and their relation to the mental faculties:

From the very earliest ages a belief in the existence of disembodied spirits has prevailed more or less forcibly among the human race there is perhaps no nation or tribe in the world many of whose members do not implicitly believe in the appalling influence of some species or other of ghost or goblin. […] A modern writer has endeavoured by the aid of physiology to ascertain whether these extraordinary and terrific impressions cannot be explained from the acknowledged laws of animal economy independent altogether of supernatural cases […]. From the peculiar disposition of the sensorium he conceives that best supported stories of apparitions may be completely accounted for. Arguing upon this assumption […] he establishes a generic disease which he terms Hallucinatio.

(‘Vathu’ 366-7)

Like a magician who deliberately shows how the trick is done, Richards brings his own medical training to the table, pitting atavistic believes in ghosts and goblins against the rational thought of the modern man of medicine. In this, Richards follows established conventions as Ruth Parkin-Gounelas points out that ‘hyperbolic emphasis on “truth” and “probability” as a prelude to the revelation of the “miracle” was a common device at the opening of early-19th-century ghost stories’ (217). In other words, the presentation of the medical argument is not only part of the magician’s sleight of hand, it is even expected of him:

That the universal opinion already adverted to should spring merely from a delusion of the senses dependent upon a disordered imagination is a circumstance which I could never bring myself fully to acknowledge and numberless are the scoffings to which my scepticism on this point has exposed me.

(‘Vathu’ 367)

The deliberate authorial self-insertion not only pulls the story into the present of the reader, but also aims at obscuring the fictional nature of the actual ghost story in the same manner as other cotemporary Gothic fictions present themselves as the very ‘authentic information’ noted by Aaron. I speak here of authorial self-insertion rather than a first person narrator, as the fascination with death portents clearly formed a staple interest for Richards for at least a decade. In the same year as ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathu’ appeared in the Brighton Gleaner, Richards submitted a piece ‘On the Popular Superstitions of the Welsh’ to The Edinburgh Magazine and a further essay titled ‘On Spectres or Apparitions’ in The European Magazine and London Review which he signed off under the pseudonym ‘Medicus’. In both pieces he states his scepticism in contemporary attempts by fellow medical practitioners to rationalise supernatural encounters as entirely pathological hallucinations. In 1830, he revisits the topic in his essay ‘The Philosophy of Apparitions’ not for the final time, but perhaps at his most blunt in terms of expressing his scepticism as he declares:

These death tokens are very curious, but they may be physically accounted for by the great and intense anxiety of the seers, directed in most instances towards these objects whose dissolution is portended. But, connected with this subject, “there are more things in heaven and earth, than are dreamt of in our philosophy”.

([Richards] 40)

What is more, in ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathu’, Richards cleverly rationalises faith and religious thought to convince the sceptic by asking, ‘Why should we not infer from the unceasing goodness of the Creator that he would present to us so decisive a proof of the immortality of the soul’ (‘Vathu’ 367). In this, Richards invokes the earlier Independent preacher Edmund Jones who, in his Relation of Apparitions of Spirits in the County of Monmouth, and the Principality of Wales (1780), similarly argued ‘In the Corpse-Candles and the Kyhirraeth, therefore we have a double testimony of the being of Spirits, and the Immortality of the soul. The one to the eyes, and the other to the ears of men’ (94). For those not immediately familiar with either of these Welsh spirits, corpse candles take the form of small hovering lights and are said to appear after the cyhyraeth, a disembodied groan or wail, both functioning as death portents for those who see or hear them. Following this diversion to the medical and theological discourses of his time, Richards finally introduces a gentleman friend ‘residing in Wales, whose veracity cannot be questioned’ (368) to establish that the ‘Pont Vathu’ haunting which the reader is about to encounter is, indeed, the honest eyewitness account by someone who is above reproach and who experienced a true ghostly encounter in recent times.

The ghost story itself is of standard fare. During a stormy autumn night, an unidentified Welsh gentleman travels from Tywyn home to Dolgellau, but is overtaken by a storm. He finds shelter in a public house at Pont Fathew and intends to wait out the storm with other patrons equally stranded as himself. One of them remarks that it is twenty years to the day that Ellen Owen of Ynysmaengwyn died during a stormy night just as this and that her supposed murderer, Evan Davies, had disappeared that day. Immediately after relating the events, the assembled guests hear a bloodcurdling scream, rush out into the night, to find a red light encircling a man drowning in the river. Having failed in their rescue attempts, the company search his pockets and discover that he is Evan Davies together with evidence that it was indeed he who had strangled Ellen after she had rejected his advances. It is a simple plot, but effectively told as it easily blends landscape and nature writing with unassuming descriptions of average country life in a Welsh backwater.

Similar to his other short stories, Richards presents the Welshness of the location, the characters or even the supernatural occurrence as par of the course rather than eccentricities. By the time of the story’s first publication in 1823, he had lived in England for 14 years and had received a thoroughly English education. For that matter, he interlaces the story throughout with several extensive quotes from English literature, such as Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Edmund Spenser’s ‘Ministry of Heaven’ or James Thomson’s poem ‘Winter’ from the cycle The Seasons, even in the supposed eye-witness account by the unidentified Welsh friend. Stephen Knight argues that until the mid-nineteenth century, Wales appears in English fiction as a colonised space and that Welsh writers until then produced ‘imperial narratives with some first-contact features’, thus effectively retaining an essentially English superior point of view over their Welsh subject by ‘revealing the dangerous and contemptible side to the natives’ (4, 164). In that vein, some aspects of the culturally adverse effects of contact between natives and the English do appear in Richards’ tale, notably as he sets the scene for his haunting:

Of all the districts in the wild, but beautiful, county of Merioneth undoubtedly that, which I was then traversing, is the wildest. It may be justly called the Highlands of Merionethshire; and the peasants have bestowed upon this desolate tract the name of Fordd ddu, or the Black Road. Being entirely out of the usual route of English travellers, its inhabitants have retained their language and their custom almost in their pristine purity; and the rugged hills which enclose them have hitherto presented an impenetrable barrier to the innovating effects of cilvilization.

(‘Vathu’ 368)

I would argue, however, that Richards uses the quasy-colonial language against itself. Despite his long absence from Wales, he refuses to portray his Welsh characters or subject as inferior, but rather gives them weight and importance. The same can be argued for his use of English, rather than Welsh poetry, not because he finds Welsh verse lacking, but, firstly, he is not well-enough acquainted with the Welsh literary tradition, and secondly, neither are his readers, the subscribers of these English literary and fashion magazines. In addition, the poetry has an emotive function of conveying mood and sentiment, instead of developing plot or narrative, hence the Hamlet quote to signal a ghost story; hence the Spenser poem to signal theological introspection; hence the quote from Thomson to signal the rustic qualities of a Welsh public house. Using English poetry for mood music whilst drawing an image of Welsh country life, he joins Scottish and Irish writers of the Romantic period who similarly used fiction to explore questions around national and cultural identities of the Celtic periphery whilst situating them within a wider, modern British context which provides ample space the simultaneous existence of more traditional ways of life in the countryside (cf. Trumpener xi-xiii).

One aspect of remote country life, which also contributes to the Gothic qualities of Richards’ tale, is the greater immediacy of forces of nature on human and animal life:

Dreadful indeed was the devastation wrought by that sudden tempest. Houses, cattle, and trees were carried away by the mountain torrents, and the woods and meadows by the river’s side were overflowed with water for many days afterwards.

(‘Vathu’ 371)

On the one hand, Richards’ description of a landscape at the mercy of the elements is merely factual, as the valleys of the area are prone to flash flooding during and after torrential downpours even today, thus representing a real danger to the local population as well as the livestock grazing in the valleys and on the hillside.

On that terrible evening there was assembled at the Blue Lion at Pont Vathu, several individuals, who took shelter from the tempest as they were returning from Towyn market. Once they thought, when the storm was at its height, that they heard a shriek near the house; but looking out, they could see nothing in the thick darkness, and hear nought, but the splashing of the troubled waters, and the soughing of the furious wind.

(Richards, ‘Vathu’ 371)

On the other hand, the storm in which Ellen perishes appears to externalise the violent character of her murderer, Evan, whose ‘disposition was as brutal and passionate as his manners were boisterous and dissolute’ (‘Richards, ‘Vathu’ 370). Even before the murder takes place, Richards notes the unusual severity of this particular storm ‘such as is rarely seen even in that district of storms’ (‘Vathu’ 371), thus heightening its uncanny linkage with Evan. The destructive nature of the storm as an external representation of Evan’s character eventually culminates in the ethnographic explanation that ‘murder is a crime very rarely perpetrated [in North Wales], and the simple peasants could scarcely persuade themselves that any one could exist sufficiently brutal and wicked to destroy the life of so meek and blameless a being as Ellen’ (‘Vathu’ 372). It is therefore only fitting that Evan’s mysterious disappearance from the entire district aligns with the calm after the storm, which subsequently enables the discovery of Ellen’s body, but in absconding justice, he also dooms her spirit to haunt the location and relive the crime so long as it remains unpunished:

But Pont Vathu was haunted ever afterwards by the beautiful apparition of Ellen Owen: a storm never occurred without bringing with it the troubled spirit of the murdered maiden, and there are few of the peasants of that part of the country who have not seen it struggling in the foaming waves of the river.

(Richards, ‘Vathu’ 372)

Eventually, Ellen exacts her revenge just on the night as Evan secretly returns to the district, bringing with him yet another destructive storm that has not been seen in the area since the night of the murder. However, this time, Ellen can make herself heard through ‘an almost unearthly scream’ and seen as a lurid red light, thus sealing Evan’s fate once and for all, before disappearing forever:

‘There sir!’ exclaimed several voices, ‘hear the Ghost! the Lord have mercy upon us!’ and we were all instantly and completely silent. […] It was dark as pitch, excepting that part of the river immediately above the bridge, and this illumined by a broad red light which threw a lurid upon the opposite bank, and encircled the body of a man, who seemed striving with some unseen and terrible power in troubled waters. In an instant the light was quenched, and the struggling ceased.

(Richards, ‘Vathu’ 372)

The scene encountered by Richards’ Welsh friend and the men with whom he was caught in the country tavern presents an inversion of the events that had taken place twenty years before. However, while ‘the lurid light […] seen on the river’ (Richards, ‘Vathu’ 373) does have an emotional impact on the spectators, I would argue that the uncanny effect of Ellen’s ghost strongly relates to the power of speech. Her murder by strangulation had robbed her of her power to call for help in a raging storm that seemingly conspired with Evan to silence her. The scream that the tavern guests eventually overhear twenty years after the deed just as the wind outside begins to subside represents the moment in which she exacts her revenge, thus harkening back to the story’s opening quote from Shakespeare in which Hamlet inquires of Horatio whether the ghost did speak, only to find out that it was robbed of its testimony by the rooster’s crow at dawn.

‘Phantoms […] show what is remembered,’ writes Ruth Parkin‐Gounelas in her analysis of nineteenth-century ghosts in Gothic fiction (214). Applied to ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathew’, this works both on the level of the text as well as the meta-level in terms of writerly involvement. The cyhyraeth and corpse candle only gain significance as Ellen’s death is remembered not only by the community, but also by her murderer. Her death haunts an otherwise peaceful community who had been unable to seek justice for her because Evan had absconded before the arm of justice was able to apprehend him. On the writerly level, Thomas Richards was haunted by the loss of his childhood home following the sudden death of his father and his involuntary removal from a Welsh-speaking community in rural Wales to an English-speaking boarding school in the city. For that matter, his interest in Welsh folk beliefs, customs and traditions were his very own personal hauntings that he compulsively revisited for over a decade in early adulthood through the means of writing fiction, antiquarian studies as well as his own medical study on nervous diseases which included a fascination for visual and audible hallucinations.

Works cited

Jane Aaron, ed., Cambria Gothica: Gothic Tales from Nineteenth-Century Wales (Aberystwyth: Llyfrau Cantre’r Gwaelod, 2018)

—, Welsh Gothic (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2013)

Edmund Jones, A Relation of Apparitions of Spirits in the Principality of Wales (1780)

Ruth Parkin‐Gounelas, ‘Learning what we have forgotten: Repetition as remembrance in early nineteenth‐century gothic’, European Romantic Review, 1996, 6(2), 213-26, https://doi.org/10.1080/10509589608570007

Thomas Richards, A Treatise on Nervous Disorders; Including Observations of Dietetic and Medicinal Remedies (London: Hurst, Chance and Co., 1829).

—, ‘Cambrian Sketches No. I.—The Spectre of Pont Vathew’, The Repository of Arts, Literature, Fashions, Manufactures, &c., November 1825, 6(35), pp. 268–74.

— (pseud. ‘Medicus’), ‘On Spectres or Apparitions’, The European Magazine and London Review, February 1823, 83(3), pp.115–20.

—, ‘On the Popular Superstitions of the Welsh’, The Edinburgh Magazine, and Literary Miscellany, August 1823 2(2), pp. 166–76.

—, ‘The Spectre of Pont Vathu’, The Brighton Gleaner, March 1823, 2(8), pp. 366–73.

—, ‘Wanderings in Wales. No. III.—The Spectre of Pont Vathu’, The New European Magazine, December 1822, 1(3), pp. 508–14.

Katie Trumpener, Bardic nationalism: the romantic novel and the British Empire (United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,1997)