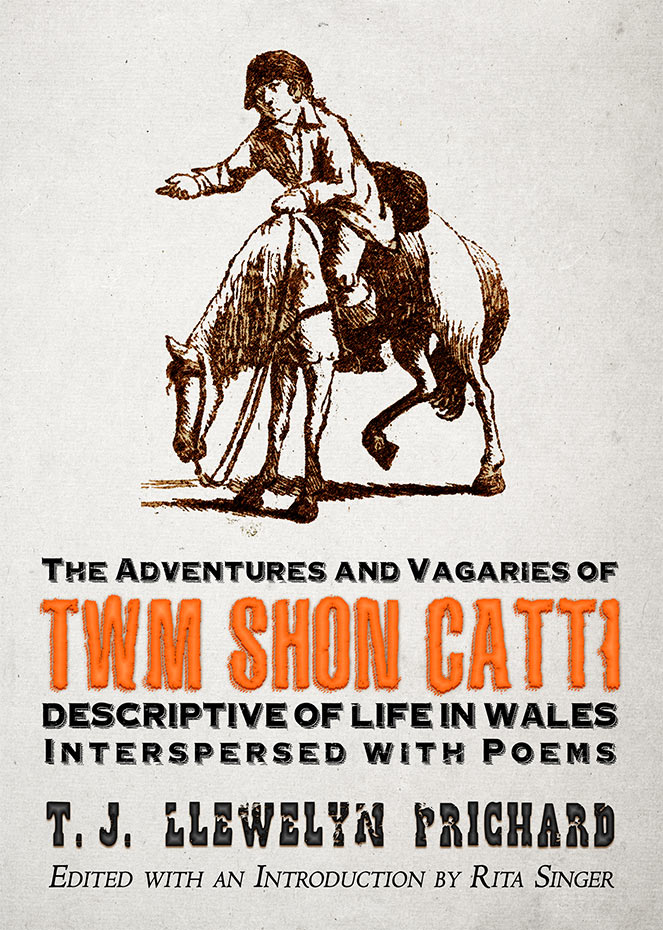

A few years back, I was very privileged in editing the first volume of Llyfrau Cantre’r Gwaelod, a new series that aims at reviving Welsh fiction that has either fallen out of print or never received much scholarly attention. Suitably, this first volume was my edition with a critical introduction to T. J. Llewelyn Prichard’s The Adventures and Vagaries of Twm Shôn Catti: Descriptive of Life in Wales: Interspersed with Poems, originally published in 1828. This romp of a novel is often referred to as the ‘first’ Welsh novel in English owing to the fact that it was written by a Welsh author, on a Welsh subject and printed in Wales. Other novels may claim the appellation of a first owing to their earlier publication dates, but none of them (as far as we know at this point) can lay claim to this particular triple achievement.

As 17 May is designated as Twm Siôn Cati Day in Wales, in light of the anniversary of the historical Twm writing his will on this day in 1609 , I’m happy to share an extract from my critical introduction to the novel here on my blog. I hope you enjoy it and may want to get hold of your own personal copy available from the magnificent Llyfrau Cantre’r Gwaelod series.

Extract:

“HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF THE NOVEL”

Although Twm Shôn Catti remained Prichard’s only novel, it remains an important contribution to a literary form that was still very nascent in Wales of the 1820s. He may not have been the most influential of Welsh novelists, but he did not miss an opportunity for self-promotion when it presented itself. In his unique style, which is at once unashamed pomposity and flattering humility, Prichard declares in the preface of the revised, second edition that

[t]he first edition of Twm Shôn Catty [sic] was received by the Public in Wales with such favour,—so infinitely beyond the Author’s expectations, that his first feeling after the book was printed, had been, deep regret that he could not afford, in a pecuniary sense, to sacrifice the whole edition, at the shrine of more matured judgment.[1]

Following from this unexpected popularity, Prichard concludes that his Twm Shôn Catti must have inevitably constituted ‘the first attempted thing that could bear the title of a Welsh novel’ because it did not ‘[betray] the hand of the foreigner’.[2] Although Sam Adams agrees with Prichard’s self-assessment as ‘the first Welsh writer to pen a novel’ (Adams, 2000, p. 7), Gerald Morgan, Jane Aaron and Andrew Davies have shown that other Anglophone novelists from Wales writing on Welsh subjects preceded Prichard by decades.[3] Among these were novels by Anna Maria Bennet (c. 1750-1808) from Merthyr, such as Anna: or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress (1785) and Ellen, Countess of Castle Howel (1794), or Fitz-Edward; or, The Cambrians (1811) by the Welsh-born ‘Emma Parker, who also wrote under the name of Emma De Lisle’.[4] Another much earlier ‘contender for the position of “first Anglo-Welsh novel” [is] Edward Davie’s Elisa Powell, or, Trials of Sensibility (1795)’.[5] However, considering that the overwhelming majority of printers and publishers of these early Wales-related novels were located in England, Prichard may well deserve the designation as a ‘Welsh first’, as he succeed in publishing Twm Shôn Catti from Aberystwyth. Nevertheless, this was not the first time that stories about Twm Shôn Catti appeared in print.

Owing to the lack of a mainstream tradition of Anglophone Welsh novels by the 1820s, the form and style of Twm Shôn Catti suggest that Prichard took inspiration from various popular literary genres from inside and outside Wales.[6] Initially handed down the generations through oral transmission, anecdotes about the historically verified Thomas Jones, Esq., (1530-1609), of Porth y Ffynnon near Tregaron, spread well beyond his native Cardiganshire.[7] In 1763, a small Anglophone pamphlet appeared in Carmarthen and Swansea under the title The Joker; or Merry Companion. To which Are Added Tomshone Catty’s Tricks. [8] The vast majority of the amusing anecdotes relate events set across the border in England. The section entitled ‘Tomshone Catty’s Tricks’ only comprises a small portion of the pamphlet, but evidently the anonymous writer found that Twm’s well-established name warranted its prominent placement on the cover page. While imprecise on some of the background of the historical Thomas Jones, The Joker constitutes an early collection of Twm’s trickeries, most of which found their way into Prichard’s novel. However, based on a letter Prichard sent to his friend W. J. Rees in 1825, it is likely that he did not take inspiration from The Joker, but from the Welsh Y Digrifwr (1811):

I am very anxious to collect information and the floating anecdotes respecting this popular Welsh freebooter. Would you be so good, at your leisure, as to translate the enclosed, and keep the original for me? (Adams, pp. quoted in 77-8; emphasis added).

Comparing the two pamphlets, it becomes obvious that Y Digrifwr is a very close translation or a pirated version of The Joker as the Welsh text contains many of the details of its predecessor, e.g. listing 1520 as yet another birthdate for Thomas Jones. It is also in Y Digfrifwr that ‘Fountain-Gate’ is not correctly identified as the Welsh Porth y Ffynnon but inaccurately translated to ‘Llidiard-y-ffynon’, the same place of birth for Twm given by Prichard.[9] These errors indicate two things. First, Y Digrifwr may have been translated from The Joker by someone uninformed about Cardiganshire place names; and second, Prichard used the Welsh pamphlet and not the much older Anglophone precursor as one of his main sources.

For the purposes of his novel, Prichard ameliorated the anecdotes contained in Y Digrifwr and other scattered tales when he assembled them into one larger body of text with a cohesive story line. Firstly, he introduced recurring secondary characters to previously unconnected anecdotes to establish narrative coherence. In this regard Twm Shôn Catti may be considered as a Welsh equivalent to James MacPherson’s Ossian and Walter Scott’s historical novels. Prichard revitalises a particular branch of the Welsh oral tradition as he adapts the material for a written literary form and populates his novel with characters from Welsh history, effectively blurring the line between fact and fiction.[10] Secondly, the novel is set in a literary version of west Wales. Originally, the anecdotes in The Joker and Y Digrifwr contained only few topographical points of reference for the reader. In contrast, Twm Shôn Catti is filled with the names of farms and estates, villages, towns and counties commonly associated with Twm in the folk tales of west Wales and Thomas Jones among antiquarians.

In addition to strictly topographical denotations that allow readers to find their directional bearings, the symbolic function of Cardiganshire, Carmarthenshire and Breconshire is similar to ‘merry England’.[11] During the Romantic period, this literary trope developed into a signifier for the premodern origin of a homogeneous English national community whose folk character remains unchanged throughout history.[12] In Prichard’s hands, the three counties subsequently represent the home and heartland of the gwerin, originally designating ‘a noble if simple people forming a classless and unified community’.[13] The gwerin are further identified by their shared use of the Welsh language, widespread communal participation in customs and traditions and a generally inward‑looking, rural life style as opposed to the metropolitanism of the Anglophone city. Prys Morgan argues that the later symbolic usage of the gwerin as a mythical signifier for the imagined Welsh national community originated in the 1880s to 1890s.[14]

While Prichard does not yet use the term gwerin, the socio-cultural dynamics between individual characters strongly suggest that he already has this mythic idea in mind. In his representation of the rural population of west Wales, he idealises the unbroken link between the land and a people who share the same language, a similar way of life and a comparatively egalitarian community structure. Prichard’s literary treatment of the Welsh as gwerin, even with all their individual shortcomings, also reflects the little that is known about his own humble upbringing in the late‑eighteenth and early‑nineteenth centuries when Wales was largely ‘a poor country, with a small rich gentry class lording it over a desperately poor peasantry’.[15] Owing to Prichard’s ‘merry-Englandisation’ of west Wales, the novel revels in its eccentrics, such as the unscrupulous Wat the mole-catcher, the jovial magistrate Prothero or the merry widow of Ystrad Fîn, often on the brink of cliché. Together they form a gwerin whose values proclaim an older popular culture of the Welsh: artless, childlike, irregular, feckless, uneconomical, merry and colourful, a culture of alehouse and churchyard sports, of ballad and dance, harp and fiddle and folktale, colourful customs, often violent sports and carousals.[16]

These values conflict with the popular imagination of the gwerin in the second half of the nineteenth century owing to the broadening influence of Nonconformism with its more Puritan outlook on community life. While Prichard’s life and writings largely reflect the ideal of the land‑bound, educated, cultured and methodical Welshman, the characters in his novel defy the later image of the religious, temperate and law-abiding gwerin of the chapels.[17]

Although Prichard located the action of Twm Shôn Catti in late-Elizabethan and early-Stuart Wales for the purpose of writing a quasi-historical novel, the novel’s ideological undercurrent is inspired by the political and social radicalism of the Romantic period. The Puritanism depicted in Twm Shôn Catti is a thinly veiled attack on the Methodism of the 1820s which, Prichard felt, turned the Welsh either into killjoys or antisocial madmen living on isolated mountain farms. He appropriates Twm’s trickeries to rebuff the ‘puritanic gloom’ of Methodism in Wales at his own time which effectively stifled the ‘mirth and minstrelsy, dance and song, emulative games and rural pastimes’ of older times (p. 19).The novel’s value system is therefore a deliberate ‘“counter-construct’, an antidote to the infectious ideology of a rapidly developing puritan culture’.[18] Consequently, Methodists are quickly cut to size by Twm himself or by their peers:

Here the little round woman retorted on her spouse, assuring Twm that he was a miserable dreamer whose brains had been turned by the ravings of fanatical preachers; that some months ago he ran three miles howling, thinking he was pursued by the foul fiend, when it turned out to be only his own shadow: and that when a patch of the mountain furze was set on a blaze to fertilise the land, nothing could convince him that the world was not on fire and the day of judgement come, till he caught an ague by hiding himself up to the chin in the river for twelve hours. (pp. 130-1)

Not only do Methodists meet with open ridicule, but they are also shown as wolves in sheep skins. Thus, Watt benefits from his fake conversion because ‘a sedate aspect was a goodly mask for the most profitable villainy’, although his criminal conduct eventually lands him on the gallows (pp. 149, 191). Watt’s villainy, however, stands in marked contrast to Twm’s robberies. Unlike Watt, who steals purely for personal gain and murders in cold blood, Twm firmly upholds his motto, ‘War not with the weak’ (pp. 88, 151). He, too, steals and kills, but, other than the remorseless Watt, he follows in the noble tradition of Robin Hood for he takes possessions only from the rich and avaricious, and only kills in self-defence or while protecting others.

Another target for Prichard’s acerbic commentary are the land-grabbing gentry, particularly of English extraction. One such case is Squire Graspacre who, true to his name, on his arrival among the inhabitants of Cardiganshire plans

to dispossess them of their property and to take as much as possible of their country into his own paternal care. […] His master–genius now became apparent to everybody; for after ruining the owners and appropriating to himself half the country, the other half also became his own with ease, as the poor little freeholders found it better to accept a small sum for their property than to have all wasted in litigation and perhaps ultimately to end their days in prison. (p. 9)

In the figure of Graspacre, Prichard airs grievances about the rapid expansion of landed estates following the enclosure of common lands particularly in the late eighteenth century. Although the proponents of large-scale agricultural production argued for their necessity, enclosures had a devastating impact on tenant farmers and small-holders; the deterioration of grain-prices and repeated bread riots, persecutions of ‘squatters who had built tai unnos (shacks erected in a single night)’ and eviction of unwelcome tenants were the most visible effects.[19] Graspacre’s behaviour is therefore less representative of the landowning squirearchy in Wales around 1600, but instead reflects the much more recent change of rural dwelling and working around 1800. Although married to a Welsh gentlelady, Graspacre wins access to the land not by marriage, inheritance or right of birth. Instead, he buys his way into the county and subsequently defiles the Welsh heartland it with his depravity. While the lady is alive, she maintains a small means of control over Graspacre’s already lose morals, but after her death his ‘wench-hunting’ and ‘offences against religion’ grow beyond control (pp. 73-4, 85).

Despite the

squire’s moral depravity, Prichard equally recognises the cultural contribution

among some of the landed gentry in Wales ‘who exulted in tales of their

ancestors and grounds’.[20]

During the second half of the eighteenth century, a Celtic craze developed

among the educated circles, with Wales suddenly becoming fashionable not only

among intellectual circles in London, but also with early tourists travelling

on the ‘Home Tour’.[21]

These combined effects lead to a resurgence of antiquarian interest in the

history and culture of Wales. These pursuits were no longer the prerogative of

the London Welsh, but also invigorated patronage among the largely anglicised

gentry and aristocracy of Wales, although they began ‘to withdraw from the

financial patronage of Welsh antiquarian studies’ when societies took over

‘patronal duties from individual members of the gentry’.[22]

Portraying Graspacre as one of these upper-class patrons is therefore a

reminder that moral depravity does not preclude interest in the preservation of

Welsh customs and traditions. Thus it is possible for Graspacre to imagine

himself ‘civilizing the Welsh’ (p. 9) as he establishes

his dominance in his corner of Cardiganshire at the same time as he takes lead

from his Welsh neighbours and tennants. Even though he firmly holds onto his

self-proclaimed English superiority over the Welsh peasantry, over time he is

forced to observe and learn from the farmers around him as the weather and poor

soil prove more difficult to manage than expected (pp. 37-8). In the case of

Graspacre, the poor land becomes a leveller between the underprivileged Welsh

peasant and the ambitious English incomer, eroding some differences of rank in

accordance with the imagined gwerin

community. It is via this detour of land management that the squire begins

taking an interest into and later patronising Welsh folk culture. He becomes a

gender-bent fictional version of the young Lady Llanover as he populates his

‘microcosmopolitan’ Graspacre Hall with maid servants from all corners of south

Wales wearing each their local folk costumes to which he has personally added

little improvements (pp. 38-40).[23]

He also sees nothing indecent about ‘courting in bed’ (‘What!’ cried the

indignant lady, ‘would you fill the country with bastards?’—‘No madam,’ was the

reply, ‘but with as happy a set of people as possible.’), becomes a champion of

local beer brewing and enjoys the liveliness of Welsh wedding customs that

Prichard felt were already in decline by the early nineteenth century, but

merited preservation as they were visible markers of an ancient Welsh people (pp. 42, 44, 56-7).

[1] Twm Shon Catty, 1839, p. iii.

[2] (p. iii). Not only did Prichard revise and expand ‘the “Small Book”, a skeleton as it then was’ (iv) for the second edition, but he also anglicised the spelling of some place names, e.g. ‘Ystrad Feen’ (p. 192), together with various names of characters, e.g. ‘ ‘Jack of Sheer Gâr’ and ‘Morris Greeg’ (pp. 26, 79), or changed names for no apparent reason, e.g. ‘Evan Evans’ turns into ‘Inco Evans’ (p. 36). Prichard made these changes very inconsistently and without a recognisable pattern.

[3] Morgan, G., 1968. ‘The First Anglo-Welsh Novel.’ The Anglo-Welsh Review, 17(39), pp. 114-22 (p. 114). Davies, A., 2003. ‘From Fictional Nation to National Fiction? Reconsidering T. J. Llewelyn Prichard’s The Adventures and Vagaries of Twm Shon Catti.’ Welsh Writing in English: A Yearbook of Critical Essays, Volume 8, pp. 1-28 (p. 2). Aaron, J., [2007] 2010. Nineteenth-Century Women’s Writing in Wales: Nation, Gender and Identity. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. pp. 8-9.

[4] Aaron, [2007] 2010, p. 8. Davies, 2003, p. 5.

[5] Prescott, S., 2008. Eighteenth-Century Writing from Wales: Bards and Britons. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 125.

[6] cf. Thomas, M. W., 2010. In the Shadow of the Pulpit: Literature and Nonconformist Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 51.

[7] Gould, M. D., 2011. ‘Social Protest and Narrative Technique in Prichard’s Twm Shon Catty.’ In: A. L. Kaufman, ed. British Outlaws of Literature and History: Essays on Medieval and Early Modern Figures from Robin Hood to Twm Shon Catty. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, pp. 114-30 (pp. 114‑5). In the following, Thomas Jones designates the historically verified person, while Twm Shôn Catti refers to the literary character. There is some conflicting information regarding Thomas Jones’s date of birth. Prichard himself believed Jones was born in 1590. Prichard, T. J. Ll., [1828] 2017. The Adventures and Vagaries of Twm Shôn Catti, Descriptive of Life in Wales: Interspersed with Poems. Aberystwyth: Gwasg Annwn. p. 7. This claim was immediately refuted by Idrison (William Owen Pughe) in his curt review of the novel: ‘The biographer fixes upon 1590 as the year of the birth of him whose life he gives, which must be twenty years too late.’ (Idrison [Pughe], 1830, p. 225) As recent as 1998, N. de Bar Baskerville tentatively gives ‘fl. bet. 1572, died 1608/09’ as his life dates. Baskerville, N. d. B., 1998. A Matter of Pedigree: ‘The Family and Arms of Dr John Dee Baptised in Wine.’ Trafodion Cymdeithas Sir Faesyfed / Radnorshire Society Transactions, Volume 68, pp. 34-52. (p. 47) The Dictionary of Welsh Biography presents 1532 as possible birthdates in the first article on Thomas Jones, but changed this to 1530 in the updated entry. Jenkins, A. D. F., 2001. ‘Jones , Thomas.’ In: Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Aberystwyth: Wales, Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru / The National Library of Wales. n.p.

[8] Anonymous, 1763. The Joker; or Merry Companion. To which Are Added Tomshone Catty’s Tricks. Carmarthen: Printed by J. Ross and R. Thomas, in Lammas-Street, where printing in general is perform’d in the neatest manner. Also sold by M. Bevan, Bookseller, in Swansea. pp. 2‑3.

[9] Anonymous, 1763, p. 25. Anonymous, 1811. Y Digrifwr. Casgliad o Gampiau a Dichellion Thomas Jones, o Dregaron, yn Sir Aberteifi; Yr hwn sydd yn cael ei adnabod yn gyffredin wrth Twm Sion Catti. Hefyd Chwedlau Digrif Eraill.. Carmarthen?: Jonathan Harris?. p. 2.

[10] Lindfield-Ott, K., 2011. ‘See SCOT and SAXON coalesc’d in one’: James Macpherson’s’ The Highlander in Its Intellectual and Cultural Contexts, with an Annotated Text of the Poem.’ PhD-thesis. St Andrews: University of St Andrews. pp. 127-8.

[11] cf. Thomas, 2010, p. 52.

[12] Blaicher, Günther. 2000. Merry England: Zur Bedeutung und Funktion eines englischen Autostereotyps. Tübingen: Narr. p. 54.

[13] Pitchford, S., 2008. Identity Tourism: Imaging and Imagining the Nation. Bingley: Emerald. p. 24.

[14] Morgan, P., 1986. ‘The Gwerin of Wales—Myth and Reality.’ In: I. Hume & W. T. R. Pryce, eds. The Welsh and Their Country: Selected Readings in the Social Sciences. Llandysul: Gomer Press, pp. 134-52 (p. 135).

[15] Morgan, 1986, p. 141.

[16] Morgan, 1986, p. 141.

[17] Morgan, 1986, p. 139.

[18] Thomas, 2010, p. 51.

[19] Davies, J., [1990] 2007. A History of Wales. 5 ed. London: Penguin Books. p. 325.

[20] Jenkins, B. M., 2017. Between Wales and England: Anglophone Welsh Writing of the Eighteenth Century. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 143.

[21] Davies, [1990] 2007, pp. 337-8.

[22] Jenkins, 2017, p. 166.

[23] ‘Microcosmopolitan thinking is […] one which in the general context of the cosmopolitan ideals […] seeks to diversify or complexify the smaller unit. In other words, it is a cosmopolitanism not from above but from below.’ Cronin, M., 2004. ‘Global Questions and Local Visions: A Microcosmopolitan Perspective.’ In: A. v. Rothkirch & D. Williams, eds. Beyond the Difference: Welsh Literature in Comparative Contexts; Essays for M. Wynn Thomas at Sixty. Cardiff: Wales University Press, pp. 186-202 (p. 191).