Summary

'Sunrise from Cader Idris' relates an ascent of the mountain at night and the sharing of a few ghostly stories as the young people await the break of dawn at the summit.

This is the second installment in a series of six short stories by Thomas Richards originally published in the New European Magazine between 1822 and 1823. As there are currently no digital editions of this small and extremely rare magazine available anywhere, I am editing my way through the collection and will publish them one by one here on my website in the upcoming weeks. In sequence, the stories are:

- No. I.—THE FUNERAL.

- No. 2.—SUNRISE FROM CADER IDRIS.

- No. III.—THE SPECTRE OF PONT VATHU.

- No. IV.—ANNA OF LLYNN.

- No. V.—THE GIPSIES OF MOWDDWY.

- No. VI.—THE SNOW STORM.

The short story ‘Sunrise from Cader Idris’ is dressed in the shape of travel writing, describing how a group of young people are setting out from Dolgellau with the intent to watch the sunrise from the summit of the mountain. They are guided by an elderly local shephard who knows the terrain and its associated stories like the back of his hand. Richards did produce actual travel writing about such an excursion for the Cambro Briton in 1820. However, in this case, the scenario lends itself perfectly so craft two folkloricy vignettes about strange and ghotic occurrences associated with spending a night on the summit.

WANDERINGS IN WALES.

No. 2.—SUNRISE FROM CADER IDRIS.

Towering from Continent or Sea,

Where is the Mountain like to thee?—

The Eagle’s darling, and the Tempest’s pride,—

Thou!—on whose ever-varying side

The shadows and the sun-beams glide,

In still or stormy weather.— Wilson’s Isle Of Palms.

There are few spectacles so gorgeously magnificent as that witnessed in the Sun’s uprising from the summit of a lofty mountain. It is a sight which calls forth every sublime emotion of the soul, and impresses us with a powerful conviction of the existence and mercy of that mighty Creator, at whose behest the whole earth is illumined with a light by far too vivid and brilliant for the eye of man to gaze at. During the early part on of my life, I resided for some time at a little town in Merionethshire; and I more than once spent the summer’s night on the neighbouring mountain of Cader Idris, that I might see the sun rise into the blue heavens in the morning. It was not then, nor is it, I believe, now, an uncommon practice, for the young men of the vicinity to ascend the mountain on a bright moon-light night in parties of seven or eight, and to sleep on the summit, returning home soon after sun-rise. We,—for I was generally of the party,—took with us a basket of provisions, with a bottle or two of good ale,—wine and spirits do not agree so well in these altitudes—and as there was a sort of cave1 on the mountain, we were always very comfortable and happy. I remember accompanying a very large party on such an excursion, on a most beautiful moon-light night in July, 18**, when there were fourteen of us altogether, including five English travellers, and our excellent and eccentric Guide, poor old Robin Edwards. We had previously arranged to assemble at the Lion shortly after eight o’clock, and were all ready to set off before the church bell had tolled nine. Having secured a plentiful supply of provant, and settled all preliminary matters, we commenced our journey; and a more imposing cavalcade scarcely ever traversed the straggling streets of our Welsh town. Had the Persian Ambassador, or the grisly Bonassus, or any other curiosity been with us, we could not well have had a greater number of spectators. Both sides of the ‘Great Street’, as it is called,—Reader, it is somewhat wider than the Old Bailey, and a little longer!—were lined with all sorts and conditions of human beings. This was a triumphant moment for our Guide,—for he, of course, led the van, and rode with all the pomp and gravity of a Generalissimo at the head of our little party. He would condescend to speak to no one, although several were the salutations which he received: but he had more important matters to think of; and it was not to be expected, that a man who had in his custody a dozen mortals, who were constrained, at least for that night, to obey his very nod, should or could stoop to any familiarity with the profanum vulgus. Robin had a distinguished character to maintain, and he did maintain it.

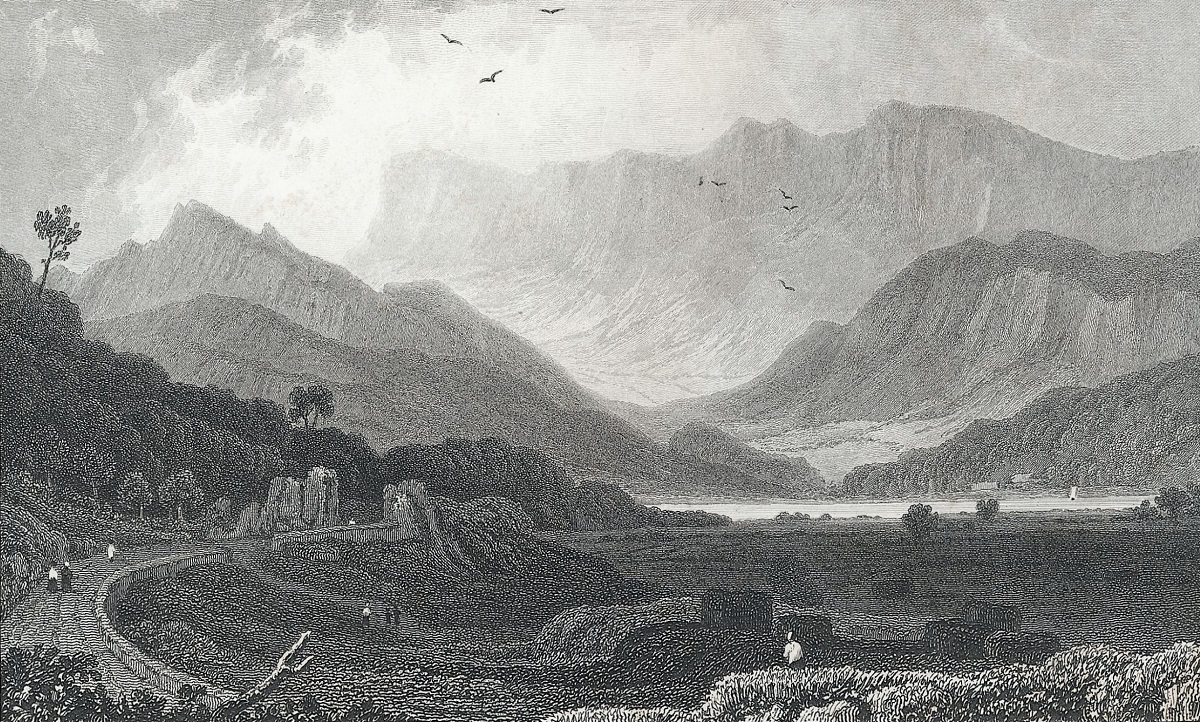

The usual road from our starting post to Cader Idris is rather desolate; it winds over the barren hills southward of the town, traversing an extensive mountain track, enlivened but at intervals by patches of interesting scenery. Good company, however, imparts cheerfulness, even to the desert, and had the paths we journeyed over been even more desolate, we should have been happy and joyous; for we travelled on among those wild hills scarcely conscious of their sterility. It was a most beautiful night; and when we first set out there was just enough light remaining to enable us to go safely on our way. But we had not proceeded far before the moon arose, filling the lonely vallies with a light even more beautiful than that of day. Her pale beams shone with brightness on the dark summits of the mountains; and the dark blue sky, with all its glittering stars, seemed to canopy us as with an imperial mantle. Beneath were the dark forests of unvaried hue, occasionally enlivened by the star-light lamp of the woodman’s cottage; and lower still, in the very bosom of the vallies, lay the placid lakes, reflecting the rays of the moon as she smiled in her loveliness above them, and falling in a column of liquid silver on the glittering waters beneath. We journeyed along, with Robin at our head, and after traversing six miles, reached the base of Cader Idris, whose majestic summit towered proudly and loftily in the heavens above us, shrouded in silvery mists, and partially illumined by the soft light of the moon. Here our party separated, those who were on horseback following a less precipitous path than that which we pedestrians were preparing to encounter. We were to meet again at the cave on the summit, and wended our way up the steep and craggy sides of Cader Idris. After clambering over many a rock, and wading more than knee deep through the fragrant heather, we found ourselves on the undulating summit of the Parnassus of Cambria; and, looking towards the west, could descry the remainder of our party moving slowly along, and just discernible in the moonlight. They soon joined us; and entering the cavern, we seated ourselves round the rude table in the centre, and believed prepared to attack the provisions which we had brought with us, as the keen air of the hills had sharpened our appetites, and rendered refreshment necessary.

Our little party completely filled the cave; and now that we were all assembled, and placed face to face, every feeling of reserve was banished, and while the English strangers made themselves universally agreeable we vied with each other in attentions to them, so that each party benefited by the society of the other, and all were comfortable. I have constantly observed, during my ‘Wanderings in Wales’, that there is in the disposition of the Welsh such an engaging spirit of hospitality, and such redundancy of free and warm-hearted suavity, as absolutely to forbid any thing like restraint. There is in their manner a total absence of that frigid formality, which is always repulsive, and usually indicates narrowness of mind; but there is abundance of that genial and attractive harmony, which is usually found among the better informed inhabitants of a secluded country. A stranger will feel, in the company of a Welshman, none of that awkward restraint which a person so frequently experiences when he is suspicious of having intruded upon another’s privacy, because he will become speedily convinced that he is perfectly welcome. I have myself so often experienced this urbanity, that justice and gratitude alike prompt me to record it; but to return.—

It was, as I have before said, a lovely night; but though all nature was reposing without the cave, I cannot say that we were equally quiet within. To speak candidly, the potent Cwrw2 which we had brought with us tended not only to dispel all gloom and quietude, but also to counteract the fatigues of our walk, so that after we had demolished a reasonable quantity of ham and beef, and swallowed a tolerable dose of Cwrw dda, we were all in the merriest mood imaginable, and so far from feeling weary or sleepy, experienced that happy buoyancy of spirits which an enlivening glass and cheerful company never fail to create. There was one of our party, young Roberts, of Cwn Coed, if I remember rightly who was well versed in the traditionary lore of the neighbourhood; and as we were then on a spot ‘pregnant with incident’, and replete with tales of superstition and credulity, our conversation naturally adverted to such topics.

At a very short distance from our resting place there is a large rock with a tolerably level surface, which has from time immemorial been considered as the couch or bed of the gigantic and princely individual from whom this noble mountain derives its name.3 Beneath this lofty crag is an irregular enclosure of stone, the remains, as it would seem, of some rustic tomb or carned; and tradition has fondly bestowed upon it the appellation of Bedd Idris, or the Grave of Idris. I will not now attempt to dispute the authenticity of this fact, suffice it to say, that such is the general opinion among the peasantry. Since the death of the guardian of this rocky fortress, this lonely spot has become doubly hallowed in the estimation of the neighbouring rustics, by being frequented at certain seasons by the Tylwyth lêg [sic], or fairies, whose nocturnal revels have been witnessed by more than one individual, and were formerly believed to be far more frequently performed than they are now. There is, certainly, something exceedingly impressive in this lonely and desolate enclosure,—situated, as it is, on the lofty summit of this magnificent mountain,—and it has a virtue attached to it, the efficacy of which I have myself tried ere now, though, I cannot say, with any sort of success. It is said, that whoever reposes within its consecrated limits, will awake either bereft of his senses, or gifted with all the sublimities of poesy:

—‘And some, who pray’d the night out on the hill,

Have said they heard,—unless it was their dream,

Or the meremurmur of the babbling rill,—

Just as the morn-star shot its first slant beam,

A sound of music, such as they might deem

The song of spirits,—that would sometimes sail

Close to their ear, a deep, delicious stream,

Then swept away, and die with a low wail;

Then come again, and thus, till Lucifer was pale.’

I have in vain endeavoured to discover the origin of this strange credulity; but such is the fact; and there is scarcely a native who has not tried the charm, to the manifest refutation, by the way, of the alleged efficacy of the virtue, for I will take upon me to say, that the only mad-man in the neighbourhood has never been up the mountain,—and as to the alternative of the spell, there is but one Poet in the place, and his effusions,— as and beautiful they are,—have been entirely confined to his native language. So much for a question which I have heard argued with all the violence of polemical controversy, and which remains to this day undecided.

Roberts related a strange story on the subject of this enclosure, the hero of which his father knew well, and was one of the few who witnessed the sequel of the adventure. There was a bold spirited fellow of the name of Morris Edwards, who used to boast that there was nothing in this world which he dared not hazard, and nothing in the other which would frighten him. Numberless stratagems had been put in practice to prove the truth of this assertion, and their results evinced that he was no vain braggart. One winter’s evening he was sitting smoking and drinking ale, as the custom then was, with a party of young men, in the parlour of the Golden Lion, when the conversation, as usual, turned upon the enclosure on Cader, and those who had subjected themselves to the influence of a nap within the sacred circle. Edwards laughed at the idea, and treated with the most sublime contempt all the superstitious notions concerning it. He had already consumed a tolerable portion of strong ale, and in the pride of his heart, offered for a trifling wager, to set off immediately, cold and cheerless as the evening was, to pass the night upon the mountain. His companions, who had not flagged in their potations, instead of dissuading from so rash and dangerous an enterprize, eagerly accepted the wager, and he forthwith prepared to set out. But just as he was about to leave the inn, one of his companions asked, what proof were they to have of his having accomplished his purpose? ‘Oh!’quoth Morris, ‘do not doubt me. I have said it, and I will do it, happen what may. Think you I fear your fairies and devils? Not I, truly; and as for the walk, why the cwrw will keep the cold away, and I’ll sing songs, and think of pretty Gwyn [sic] Rees till I fall asleep; this cloak,’—wrapping round him a large horseman’s coat,—‘will serve for a covering, and I’ll find a mossy stone for a pillow, depend on’t, so farewell, and—‘

‘No, no, Morris! this won’t do;’ interrupted the other; ‘It is all very well to talk in this manner; but we must have some better proof of your bravery than this boasting. Take this knife, and leave it on Pen y Cader, (the top of the Fort), and there will be then a proof of your valour.’ This was soon acceded to; and Morris the mad-brained, as he was often called, set out on his journey, two or three of his companions agreeing to walk and meet him early the next morning. The evening was cold and gloomy, and the thin, watery-looking clouds seemed ready to discharge their contents so soon as the night-wind should fall. There was a moon, it is true, but her light was so often obscured by clouds, that she afforded the adventurer but little assistance; so that had not every rood of the road been well known to him, he would have found the task of ascending the mountain not only arduous, but impossible. As it was, he had no trivial risque to run: had he been overtaken by a storm he would, most probably, have been buried alive in the drifted snow; and although the night were ever so calm and lovely, one false step would, in many parts of the mountain, have sealed his doom. However, Morris Edwards was as active and ardent as he was resolute and rash; and with a long hunting-pole as his support, he boldly pursued his course on this perilous enterprize.

Early the following morning two of his companions walked along the road, leading to the mountain, to meet their friend, and to witness the effects of their exploit. They had walked about two miles, when they discovered in one of the windings of the road, and at some distance before, a human figure running with all his might towards them. He used almost unearthly speed in his progress, and appeared through the grey mist like one of the mountain genii, flying on the wings of the moving wind. They soon discovered that it was Morris Edwards, and were greatly alarmed at his hurried and fearful appearance. They stood still, and awaited his approach, and, when he reached the spot where they stood, prepared to salute him, expecting that he would stop. But he heeded them not, and bounded along the rocky way as if life and death depended upon his speed. There was a wild, unearthly glare in his eye, which told, plainer than any words could have done, that something unusually terrible had happened to him; and his two friends,—one of whom was the relator’s father,—retraced their steps to the town, and hastened towards the dwelling of Edwards’s mother. On their arrival they found their friend reclining on a settle by the fire-side, perfectly insensible, and apparently lifeless, the only indication of the existence of vitality being occasional twitchings of the face, and a hard and deep-drawn sigh. He remained long in this miserable condition; and notwithstanding the administration of various medicines, no symptoms of recovery were perceptible till towards the evening, when he opened his eyes and spoke incoherently to those around him. A severe fit of sickness was the consequence of this adventure, and long did he languish under its influence What had happened to him on the mountain nobody could ever discover. To some pressing enquiries put to him by a particular friend during his convalescence, he replied—‘If you wish to continue my friend, you will not speak to me on this subject; if you persist in your importunities, you will know what to expect from one who will consider himself insulted.’ After this no one asked further, but a variety of conjectures, were, of course, hazarded. What had really happened to him was never known; and whether he actually saw some supernatural apparition, ‘some God, some Angel, or some Devil;’ or whether his imagination, aided by the desolateness of his situation, as well as by the awful stillness of the night, had conjured up some terrible phantom, nobody could say. Something unusual had certainly occurred to him, for his future life was materially influenced by this nocturnal adventure; and it was observed by all, that he who was wont to be called Morris the mad-brained, had become altogether a gentle and an altered man.

‘He went like one that had been stunn’d,

And is of sense forlorn:

A sadder and a wiser man,

He rose the morrow morn.’

By the time young Roberts had related this strange story, the first faint dawn of morning appeared behind the eastern hills, and we consequently left the cave to seek some more elevated spot, whence we might witness the glorious rising of the God of Day. We soon arrived at an eminence commanding a clear and extensive prospect in all directions; and with our faces towards the East, we waited the appearance of the Sun with as much anxiety, and, perhaps, with as much devotion, as a congregation of Persians.

There was something most sublimely beautiful in the scene. Before us were numberless hills, down whose rugged sides the morning mist rolled in murky volumes, till it spread over the green vallies beneath like a fair fleecy mantle; while, in every other direction the mountain reposed in the gloom and stillness, to be dispelled only by the genial rays of that luminary which was rising to renew the mingled cares and pleasures of a large portion of the habitable globe. Not a cloud was there to dim the bright blue of the sky, and the stars, as they gradually disappeared at the approach of day, twinkled less and less brilliantly in the heavens. And now a brighter glow appeared in the East, spreading far and wide over the sky, till the first faint beams of the sun arose to illumine the earth, and to diffuse light, and life, and joy over the hills and vales around us.

‘The morn is on the hill; the Eastern red

Breaks, blushes, burns, o’er Earth and Heaven is spread;

The breeze, that at the dawning lightly gave

Its gentle motion to the purple wave,

Just shook the heather on the mountain’s side,

Just breathed along the vale,—the breeze has died.’

We tarried long to gaze at the glowing scene before us; and it was not until the sun had ‘clomb into the heavens high’, that we bade adieu to Cader Idris, and returned home highly gratified with our adventure.

1This Cave is an excavation, the sides of which are composed of mud and turf, while the roof is solid rock. A mass of stone placed in the interior, and surrounded by a seat of turf, answers every purpose of a table; and rude and cheerless as this cave may appear, it has echoed and re-echoed to many a merry revel.

2Cwrw, which must seem a very unintelligible word to an Englishman, is the Welsh for Ale, and is pronounced Cûrrû.

3Cader Idris signifies the fort or dwelling-place of Idris, who was,—according to tradition,—a gigantic prince of former ages. Various tales are related of him by the peasantry; and we may, perhaps, at some future period, present the Readers of the New European with some of the many traditions respecting this worthy, and Cader Idris generally.